After multiple viewings of Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day, I still get confused by some of the details of the gang activity, but there’s little doubt that it’s an artful disorientation, mirroring the directionless, unproductive stasis of the posturing and skirmishes. The young people at the centre of the movie feel the possibility of a new paradigm – they listen to Elvis and lap up local cover bands (at least some of whom have to learn their lyrics phonetically); they play pool and hang out – but Taiwan of the early 60’s doesn’t have the open horizons (however illusionary those may ultimately have been) of the America of the same period: school is a more regimented affair, symbolized by the wearing of numbered military-style uniforms, and the economy is sputtering, with the age of supercharged growth still ahead. The troubled protagonist, Si’r, embodies the fractures and limitations: in a different environment, his rebellion would no doubt be transient and containable, but here he’s drawn back toward transgression, through violence and lashing out but also more subtly by an overly romantic view of women, a concept of purity that when denied, leads him into extreme tragedy. His parents live through their own more restrained sadness – his father passing through McCarthy-like interrogation and with the loss of a familiar role within government, poised at the end to enter the uncertain world of private enterprise. The film’s scheme also includes a movie studio situated next door to the school, an easy lure for cutting class, and adding a further layer to its theme of searching for truth and authenticity – Si’r at one point gets to lash out at the in-house director for his lack of perceptiveness. The film’s almost four-hour length reflects an underlying sense of heaviness, of a society in which true distinctive momentum is going to be hard to come by, and yet the film itself is hardly a heavy viewing experience, ventilated by Yang’s deep curiosity and engagement.

Saturday, December 28, 2019

A Brighter Summer Day (Edward Yang, 1991)

After multiple viewings of Edward Yang’s A Brighter Summer Day, I still get confused by some of the details of the gang activity, but there’s little doubt that it’s an artful disorientation, mirroring the directionless, unproductive stasis of the posturing and skirmishes. The young people at the centre of the movie feel the possibility of a new paradigm – they listen to Elvis and lap up local cover bands (at least some of whom have to learn their lyrics phonetically); they play pool and hang out – but Taiwan of the early 60’s doesn’t have the open horizons (however illusionary those may ultimately have been) of the America of the same period: school is a more regimented affair, symbolized by the wearing of numbered military-style uniforms, and the economy is sputtering, with the age of supercharged growth still ahead. The troubled protagonist, Si’r, embodies the fractures and limitations: in a different environment, his rebellion would no doubt be transient and containable, but here he’s drawn back toward transgression, through violence and lashing out but also more subtly by an overly romantic view of women, a concept of purity that when denied, leads him into extreme tragedy. His parents live through their own more restrained sadness – his father passing through McCarthy-like interrogation and with the loss of a familiar role within government, poised at the end to enter the uncertain world of private enterprise. The film’s scheme also includes a movie studio situated next door to the school, an easy lure for cutting class, and adding a further layer to its theme of searching for truth and authenticity – Si’r at one point gets to lash out at the in-house director for his lack of perceptiveness. The film’s almost four-hour length reflects an underlying sense of heaviness, of a society in which true distinctive momentum is going to be hard to come by, and yet the film itself is hardly a heavy viewing experience, ventilated by Yang’s deep curiosity and engagement.

Saturday, December 21, 2019

Minnie and Moskowitz (John Cassavetes, 1971)

It's only by John Cassavetes’ amazing standards that a film as prickly as Minnie and Moskowitz could feel relatively conventional. It fits recognizably within the romantic comedy genre: two emotionally unsettled people meet under offbeat circumstances (he’s a parking lot attendant at the restaurant where she’s fleeing from a terrible failed date) and rapidly enter a relationship defined as much by conflict and anger as by recognizable connection. Before they meet, they’re both seen separately attending an old Bogart movie, and Minnie (Gena Rowlands) explicitly cites the gulf between silver screen illusions and turgid realities: the movie often seems to be frantically underlining the point, as Minnie’s former lover (played by Cassavetes himself) slaps her several times across the face, and the man she meets on that bad first date blurts out information about a mistake he made on his wedding night, and about his unnaturally hairless legs. Of course, such emotional rawness and behavioral extremity, the sense of people hoping to discover themselves by throwing stuff out there and seeing what sticks, is typical of Cassavetes, but in this particular case (and I emphasize again, this is relatively speaking) the effects seem a bit more studied and less deeply felt, the eventual route to each other somewhat arbitrary. But then, that’s probably part of the point, given how the film ultimately places coupledom as a form of suppression – as soon as they decide to get married, they call their respective mothers, and then sit mostly quietly through an excruciating dinner in which Seymour’s mother lays out all his faults, and then through a wedding ceremony in which the priest forgets Minnie’s name (with Cassavetes allowing himself, for once, an easy laugh). The final scene is of a teeming, happily chaotic family get-together, but who knows how much of the real Minnie and Seymour remain intact within it?

Saturday, December 14, 2019

Suspiria (Dario Argento, 1977)

It’s not hard to see how Luca Guadagnino might have become occupied by the notion of building on Dario Argento’s original Suspiria – in hindsight the film may seem composed largely of lacks waiting to be filled. Among other things, the narrator’s specificity about Suzy Bannion’s (Jessica Harper) initial arrival in Germany at 10.40 pm seems at once circumspect (where in Germany? – either way, we see no more of it subsequently than a bland modern conference centre) and strangely temporally precise (almost Kubrickian?); for a film set in a dance academy it’s odd that there’s only one brief scene of actual dancing; Madame Blanc’s (Joan Bennett) early reference to having known Suzy’s aunt is an intimation of broader purpose and connection which never comes up again; the manifestation of the threat is haphazard (why does the dog initially, from what we’re told, attack the child and then, as depicted, kill its blind owner, who doesn’t appear to be a new source of threat); the ending is overly abbreviated – a brief showdown and then Suzy’s emergence from the burning academy, leaving all kinds of visual possibilities unexplored and narrative threads untied. Guadagnino’s (rather fine) film is generally more unified in such respects, while adding a fascinating politicized element, but of course such mythologies can only ever spawn unanswered questions and challenges to one’s indulgence. The particular spell of Argento’s film may lie largely in the structuring effect of these very absences; in conjunction with the director’s often extraordinary compositions of light and framing, they create a film seeped in predestination, with Harper’s air of engaged fragility providing a perfect focal point. The film has no shortage of moments of giallo-like brutality, but its categorization as such has been debated – to me its heart seems located somewhere beyond giallo or horror, in some dreamily beautiful, semi-articulated zone of terrible destiny.

Saturday, December 7, 2019

Invasion of the Body Snatchers (Don Siegel, 1956)

Don Siegel’s Invasion of the Body Snatchers provides one of cinema’s great, ever-renewing metaphors, seeming as topically resonant in Trump’s America as it did in Eisenhower’s, although for different, almost inverted reasons. Memories of how Trump’s initial joke candidacy rapidly became a monolithic red state takeover line up nicely against the ease of the alien takeover here, a brief spate of panic rapidly replaced by mass compliance, with just a few dwindling holdouts (seen nowadays, the “pods from space” origin of the threat seems like the least important aspect of the myth). You might reflect how Trump’s humourlessness and lack of reflection, his lack of pleasure in art or conviviality, appear to be foretold in the emotionless nature of the pod people: there’s no suggestion that they plan to remake Earth in the image of their home planet, or to craft new institutions or structures - they seemingly intend just to keep going as they are, except in joylessly hollowed-out fashion (a key sign of trouble is the drop-off in business at the local restaurant). It need hardly be underlined that the afflicted town is about as aspirationally white-bread as they come, with not a hint of problematic diversity. Anyway, whether or not you choose to apply it that way, it’s a great, propulsive eighty minutes (you might certainly wish it were longer), rapidly picking up speed and panic, with Kevin McCarthy’s doctor a memorably fraught protagonist; Siegel nails both the intimate chills, such as the first discovery of an evolving pod person, and the broader spectacle of the climactic pursuit. If the doctor’s pre-invasion pursuit of an old flame who's arrived back in town seems to border on cheerful sexual harassment, well, maybe then that’s one respect at least in which the body snatchers render things a little less Trumpian than they already were.

Saturday, November 30, 2019

The Dolls (1965, Dino Risi, Franco Rossi, Mauro Bolognini, Luigi Comencini)

The Dolls (Bambole) is one of the many lesser-known anthology movies from 60’s Europe, this one with four directors but a mostly uniform tone (some of the best such anthologies benefit from a radically different contribution by Godard, but not this one). The common link in each case is frustrated sexuality, either prompted or suffered by one of the decade’s Euro-babes. In Dino Risi’s opener, Virni Lisi plays a wife who won’t get off the phone with her mother, eventually driving her ready-to-go husband into a more receptive set of arms in the adjacent apartment building. Luigi Comencini ogles Elke Sommer as she’s driven around in search of the genetically perfect Italian male to father her child, to the chagrin of the willing but rejected driver. Franco Rossi’s piece has Monica Vitti improbably married to a pathetic older drunkard, trying in vain to get someone to polish him off: the segment’s darker premise and Vitti’s recent association with Antonioni marks this as a somewhat more serious interlude, albeit still played as farce. Finally, Mauro Bolognini (in a story adapted from Boccaccio, as if that mattered) places Gina Lollobrigida as the unappreciated wife of a hotel manager; the hotel is full of priests attending an ecumenical conference, one of whom brings along his hot but oblivious nephew as his secretary, and so, well, obviously… This last segment may be the only one of the four in which the main players are all left fulfilled, without lasting consequences. The project may be scored as feminist-positive in that female desire is a stronger narrative driver here than the male; but on the other hand, the males just as often get what they want, not least of all those in the audience: the brassily fetishistic animation of the opening credits, and of course that title, say it all.

Saturday, November 23, 2019

Near Dark (Kathryn Bigelow, 1987)

It may not be plausible to argue that Near Dark is Kathryn Bigelow’s best film, but if you could only keep one of them, it might sneak in (at the last charred minute before the arrival of the dawn, just as the last remaining print is on the verge of bursting into flames). The movie has a great, confident genre swagger, leaving out huge gobs of explanation and connective material: it takes what it wants from vampire mythology and discards the rest. Basically, that means no mumbo jumbo about crosses or waiting to be invited in or suchlike, and lots of hungry, malevolent glee – these certainly rank among the most zesty, committed vampires in the canon. That said, there’s not much actual bloodsucking, and the main instance of it – Adrian Pasdar’s newly-turned member drinking from the arm of the pretty girl who turned him (Jenny Wright) – is as intimate as it is malevolent. The film doesn’t exploit or objectify its female characters though: the troop seems to function in boisterously Hawksian manner, tolerant of quirks and difference as long as everyone pays his or her way. The narrative zips around the South, depicted here mostly as an underpopulated, dusty landscape of dingy motels, bus terminals, and nothing towns – it draws on the iconography of cowboys and family-centered homesteads, of heroic showdowns against the odds. As I indicated, the rising sun might constitute a major character in itself, at several points taking the rampaging vampires (who it seems don’t hit their stride until around 5.30 am) by surprise, sending them racing in search of shelter; no doubt the relish of one’s immortality coexists with a compunction to push its limits. Pasdar and Wright convey a quietly lovely, lonely connection that places them among the most appealing couples in a Bigelow movie (not that the competition there is too intense).

Saturday, November 16, 2019

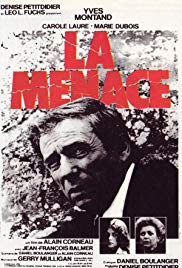

La menace (Alain Corneau, 1977)

Alain Corneau’s La menace plays out a cleverly-conceived scheme – a protagonist (Yves Montand’s Henri Savin) implicated in two non-existent crimes: the first a suicide in which his lover is implicated through coincidence; the second an elaborate ruse he devises as a route to freedom, but which works all too well, bringing him down through vigilante justice. Given all the complications, the film has relatively little dialogue, focusing primarily on action, from large-scale stunts on mountain highways to endless small manipulations: the typing of a faked letter, self-inflicting incriminating scratches, manipulating the hands of a clock and so on, the irony being that the underlying motive usually differs from the kind of malign set-up we’re used to in genre movies. In truth, it’s hard to figure out why Savin goes down this road in the first place, but perhaps the premise is that of an ill-considered initial reaction that then inexorably leads to others. The film’s climax plays out in British Columbia, where Corneau appears to have a great time marshalling heavy vehicles (this at the height of CB radio culture) on wide-open roads, although it doesn’t say much for the morals and ethics of Canadian truckers. The use of Montand in such a context presumably evokes The Wages of Fear, a movie that of course is infinitely better-remembered than La menace: for all of Corneau’s skill, the film feels rather uninvolving, partly because it’s hard to believe in the relationship between Savin and the beautiful, much younger cipher played by Carole Laure. The film hints that the investigating detective may contain his own more complex depths, but that just peters out, as does an initial subplot relating to human trafficking. Overall, it feels like Corneau’s precision and the climactic investment in spectacle should have resulted in a better-known film, but on the other hand the fate of excessive calculation leading to oblivion is an apt mirroring of its central narrative.

Saturday, November 9, 2019

Blow Out (Brian De Palma, 1981)

Blow

Out may be Brian de Palma’s most artful

indulgence of his affinity for disreputable material: it opens on an overly

prolonged, loving evocation of the slasher genre which might have been designed

to make your heart sink, but ultimately finds in such material a terrible kind

of commemoration, a recorded truth which for all its grisly artifice holds

greater integrity than the machinations of political power. The film has a classic

set-up: while capturing night noises from a bridge, Jack (John Travolta), a

movie sound guy, witnesses a presidential candidate’s car leave the road and

fatally enter the water, but no one subsequently wants to hear about the gunshot recorded on the tape, nor about the woman (Nancy Allen) he pulled from the sinking

vehicle. A large part of the pleasure comes from the immersion in old-fashioned

tangibility, in physically handling film, marking frames with an X and so on;

this and the title provide an obvious echo of Antonioni’s Blow Up, but

there’s not much of the aspirationally sensuous about De Palma’s film, not much

feeling of a time and place that will one day be looked back at with mysterious

fondness. Still, the situation allows plenty of pleasing ambiguities: for instance

in how Jack becomes the only repository of and fighter for the truth, even

though he only got into the whole thing while gathering raw material for

cinematic lies. The movie has some of De Palma’s most striking uses of split

screen, and a bravura climactic chase sequence; the narrative is well-crafted,

winding to a most bitter and incomplete kind of closure. One might wish that

Allen’s character could have been conceived in slightly more mature terms, or

that the political cover-up didn’t have to involve a gloatingly sleazy assassin

and a series of sex killings, but at least the movie’s colourful misogyny is in

step with its overall cynicism.

Saturday, November 2, 2019

Old and New (Sergei Eisenstein and Grigoriy Aleksandrov, 1929)

Eisenstein’s and Aleksandrov’s The Old and the New (or The General Line) makes now for astonishing if somewhat strange viewing, both enveloping and alienating. Following the evolution of a collective farm and the peasant woman who keeps pushing it forward, the film may stick in the mind largely as a series of set-piece milestones, such as the acquisition of the first milk separator, the first bull, the first tractor – the film establishes the specific economic significance of each step, while also positioning them as a form of dream-like release, so that the first spurting of cream becomes a fountain, one tractor becomes a formation of dozens, and the bull’s potency becomes (through a staged marriage to a flower-bedecked cow) that of the community as a whole (a visit to a modern state farm is positioned almost as a science-fiction trip to a smoothly facilitating future). But the scheme also encompasses cautionary near-nightmare: the initial application for the tractor drowns in gleefully-depicted bureaucracy, and there’s a stark evocation of witchcraft. The production history spanned a shift in governing ideology, and this results now in a film that always feels to be pushing to escape its propagandistic shackles, without denying their existence (or, to some extent at least, their validity). Few films contain as many vivid close-ups of care-worn faces, and in that respect it’s deeply humanly connected, but at other times it barely feels human at all (the villains and obstructionists often register more fully than the agents of progress). If viewed as history, then it’s a monument to a time when industrialization could be regarded as a tribute to the capacity of the land rather than as a pillaging of it; when physical labour could be alleviated without heralding a descent into narcissism; but at the same time it feels unshackled from any time and place at all, excepting that created through pure cinema.

Saturday, October 26, 2019

Idaho Transfer (Peter Fonda, 1973)

Peter Fonda’s Idaho

Transfer is a super-high-concept time travel drama that generally doesn’t

feel like it: for much of the time, we could be watching Woodstock types dawdling

on their way to the next concert (indeed, the movie early on throws in two

secondary characters doing exactly that). The premise is a project to save mankind

by setting up a colony in the future, on the other side of a looming apocalyptic

event; the time travel technology (located in a secretive desert facility) necessitates

sitting on a low metal platform, taking off one’s pants and pushing a few

buttons, and doesn’t work for people over thirty (even for them, it eventually

transpires that it causes sterility, making the whole project largely

pointless). If that explanation seems absurdly high-level, it’s about as much

as the movie ever provides: the screenplay is refreshingly free of ringing

certainties, and the prevailing mood is that of watching figures in a barren

landscape, trying to roll with the punches (Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point

may come fleetingly to mind, but everything here is far less charged, including

erotically speaking [notwithstanding the frequently absent pants]). Much of the

“action” – such as the discovery of a mutated post-disaster civilization - occurs

offscreen, and Fonda takes some big narrative leaps, but the sense of emptiness

feels well-judged given the rather despairing premise, conveying a pervasive

sense of dissipating youthful promise. The movie saves its boldest stroke for

the very last scene, reconfiguring our sense of the world we’re watching (possibly

too much for comfort, but at least it’s striking) and throwing in some grisly

implications. It’s hardly a high-impact piece of work, not so much acted as just

embodied, and one almost wishes Fonda had pushed even further in that

direction, toward pure abstracted reverie. As it is though, it’s still mostly

satisfying, in a stubbornly self-absorbed kind of way.

Saturday, October 19, 2019

Something Different (Vera Chytilova, 1963)

Vera Chytilova’s Something Different delivers exactly that, most literally by switching back and forth between two contrasting narratives: one observing Eva, a gymnast in training for upcoming championships; the other following Vera, a housewife overwhelmed by her hyperactive young son and by domesticity in general. The two strands only occasionally explicit echo each other (Vera’s husband and Eva both criticized for reading the paper, him at the dinner table and her on the beam) but provide parallel studies in the difficulty of maintaining balance (in Eva’s case, literally as well as figuratively) and resisting subjugation. Eva’s position seems more privileged by virtue of her relative fame, and yet her coaches rail at her laziness, grab at her limbs and pull her into desired poses, scornfully dismiss her ideas and instincts, and at one point slap her across the face: her final performance liberates her from such direct control, while withholding any real sense of exultation. By comparison, the sequences with Vera are a frenetic pile-up of life problems, underlined by frequent arguments about money. She starts an affair with a man who pursues her in the street, but in large part it seems like another source of life clutter, another submission to an agenda primarily set by someone else; when a crisis hits at the end, she has no option but to cling onto what she has, however unsatisfying. The film’s last sequence, with Eva now coaching a young female athlete, suggests the possibility of calmer and more nurturing structures ahead, but the final note is questioning and reflective rather than in any way triumphant. Eva’s distinct place in society relative to Vera's correlates with a greater openness to cinematic invention as measured by camera angles, freeze frames and suchlike, but these also speak to her distance from the more typical life experience.

Saturday, October 12, 2019

Prince of the City (Sidney Lumet, 1981)

A viewer could be forgiven for finding much of Sidney Lumet’s Prince of the City rather flat – it’s stylistically restrained and businesslike, with few conventional dramatic highpoints: the casting of Treat Williams (who, in truth, doesn’t seem entirely equal to the role) might have been designed to thwart easy gratification. It eventually becomes clear though that this is a strategy, and a rather subtly executed one, channeling the growing realization of its protagonist, Danny Ciello, that in his play for heroism and expiation, he’s lost all autonomy and self-determination. The movie initially emphasizes his princeliness, at the centre of a smoothly functioning drug squad unit, racking up collars while regularly bending the rules and skimming off the spoils: he’s drawn to cooperate with a probe into police corruption, seeing it in part as another stage to strut upon, naively certain he controls his exposure and that of his partners. But the film ultimately comes down to a decision on whether to prosecute Ciello himself, staged by Lumet as a debate into the interplay of relative morality, idealism and pragmatism, the final determination on which may be little more than a coin flip; it’s intercut with a court proceeding where Ciello is raked over the coals, culminating in a question about whether his wife (Lindsay Crouse) was aware of his interactions with prostitutes. It’s notable that by then, she and his children have largely faded from the film, casting it as a study in escalating loneliness – an impression sealed by the very last moment, freezing on his face in the aftermath of yet another small humiliation. Again, you might feel that final blow should land a little harder, but maybe such criticism would undervalue Lumet’s finesse – why should we expect conventionally satisfying closure, when that’s so plainly denied to the character, if not to anyone who participates in the torturous justice system?

Saturday, October 5, 2019

Weekend at Dunkirk (Henri Verneuil, 1964)

Henri Verneuil’s 1964 Weekend at Dunkirk has (to a surprising extent) pictorial qualities to match Christopher Nolan’s more recent treatment of the evacuation, with a more personal and haunting overall narrative. It was much remarked how Nolan withheld some basic information about surrounding events for instance by omitting any glimpses of Churchill, but Verneuil does something very similar, dropping his protagonist Julien (Jean-Paul Belmondo) into the middle of the action, leaving no doubt about its momentous nature, but emphasizing Julien's confusion about what’s going on (the most salient point about the British operation is that they don’t want to take the French with them) and his indecision about how best to survive without succumbing to desertion or cowardice. Beneath all the terrific spectacle and impactful incident, there’s something close to lurking black comedy in how Julien keeps finding himself back at the same point on the beach, even as others leave in one way or another (to the point that he’s ultimately the last one left): his conversations with a priest add to the sense of moral inquiry. Julien embodies all the ambiguity of war, intuitively working to strike up a mutually respectful rapport (even, eventually, with an obstructive British officer), but reacting with as much skepticism to an individual who thinks too calculatingly of his own survival as to another who too aggressively brandishes his giant gun: the only soldiers he directly kills are French ones, to save a woman from being raped, but then her subsequent actions have him wondering almost immediately whether he did the right thing. The fact that Catherine Spaak would have second billing in a film about Dunkirk perhaps sums up the commercial friendliness that influences one’s view of Verneuil, but in the end her presence adds more than it detracts, speaking to his consistent ability to create unified, textured works.

Saturday, September 28, 2019

Diary of a Country Priest (Robert Bresson, 1950)

In a lesser film, the emphasis on writing in Robert

Bresson’s Diary of a Country Priest might seem over-emphatic, almost as

a negation of cinema: for a significant portion of screen time we see the words

on the pages of the priest’s journal and simultaneously hear them in his voice

over. In Bresson’s hands however, the repetition deepens our compassion for the

meticulous thoroughness of the protagonist’s struggle, while surely suggesting

a linkage between the man of God and the artist: each consecrated to his

interpretative process, to relentless self-examination, to a journey of

uncertain destination. The film’s ultimate tragedy is embodied by the priest’s

incapacity to craft the final entry, by the intrusion (however respectful) of

the voice of another, by the yielding of all imagery to that of the cross. The

film depicts the priest’s life as small and strained, doomed almost from the

start (there are hints of what we might now call fetal alcohol syndrome), but

with the capacity to acquire a kind of majesty (or grace, in the film’s terms)

if it were allowed to approach God expansively and openly, to rely as much on

intuition as on dogma and ritual. But the rural society to which he’s assigned

is parched and grudging and set in its ways, tolerant of the church as long as

it maintains its boundaries as an abstract pillar of continuity and order and

discipline, unable to countenance true questing or suffering. The film feels so

unerringly composed that later Bresson works may almost seem strained by

comparison (this is a purely relative assessment, I should emphasize). It also

encompasses one of the purest expressions of bliss in his work – a brief ride

on the back of a motorcycle ride that leaves the priest momentarily

exhilarated, certain he feels God’s hand in the experience (it’s a moment of surrender

that may bring to mind the older Bresson’s delight in For Your Eyes Only,

for its “cinematic writing”). Diary of a Country Priest is at once resolutely

tangible and specific and wondrously transcendent, an inexhaustible filmic

pilgrimage.

Wednesday, September 25, 2019

Un singe en hiver (Henri Verneuil, 1962)

Friday, September 13, 2019

Performance (Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg, 1970)

Any attempt to briefly describe the plot of Donald Cammell and Nicolas Roeg’s Performance would have to say something about changing places, or mutually appropriated identities, or the transmigration of souls - about vice and versa as the poster put it. And yet, if measured by screen time this is a relatively minor part of the movie, and one that hardly seems to arise organically from what precedes it: it seems more likely that James Fox’s gangster Chas and Mick Jagger’s rock star might spend a few days avoiding each other before going their separate ways. It’s a tribute to the film’s druggy, ornate, discursive texture that it always feels it might slot into place (sort of anyway) with just one more consciousness-shifted try. But in practice, further viewings just yield further points of reflection and oddity. To cite just one, I always forget how far the movie goes down the path of genre, sinking with real relish into the brutally swaggering gangland world and its pretensions to external respectability – sometimes it feels as if Turner and his milieu might just be a projection, excavated from the secret heart of the violence (the intertwining of the worlds, especially in the “Memo from Turner” performance, support this view). And yet Turner’s house is so brilliantly and specifically visualized, and the languid behavioural rhythms so compelling (Chas’s probing pillow talk with the boyish Frenchwoman Lucy feels particularly authentic) that this explanation clearly won’t do: Turner embodies new propositions and realities (however undefined and faltering, as indicated by his un-Jagger-like withdrawal from stardom) that in one way or another will undermine the old certainties. The film teems with oddities of emphasis or pacing, or expression or framing, and sometimes makes you wince (that’s how the close-up of Borges makes me react anyway) and yet you might fantasize about living entirely within it.

Saturday, September 7, 2019

Le pont des arts (Eugene Green, 2004)

Eugene Green’s Le pont des arts is indeed a film of bridges: of the real-life Parisian location of its title as a site of loss and redemption, of art as a means of spanning people and worlds, of the connective raw materal of cinema itself. The film contrasts a semi-established classical singer and a disaffected philosophy student: they never formally meet, but the beauty of the singer’s art creates a bond which outlasts her personal tragedy and provides to the student a new direction and purpose (this is, no question, a misleadingly tidy synopsis). Green favours a restrained performance style and head-on, interrogative close-ups, a style which tends to emphasize the distance between people and the created nature of the narrative – when the two protagonists finally touch, the event is depicted only in shadow – but the joy in ideas, the belief in high culture as a source of transcendent beauty, are absolute (a sequence studying the audience’s reaction at a Japanese No production, and a brief encounter with a Kurdish singer, make the point that such effects aren’t confined to canonical Western glories, although the film seems more iffy about rock and roll). At the same time though, Green skewers the earthly pretensions which constantly get in the way: in particular, the singer’s milieu is depicted as overrun by grotesquely self-regarding monsters who take pleasure in making tools out of people (the film, it should be said, is often very funny in this regard). In the end, it’s both a seductive immersion in a certain type of cinematic tradition (one in which it seems meaningful that the student somewhat evokes Jean-Pierre Leaud) and an assertion of art – in that magical space where actors and acted-upon find communion – as an abiding zone of difference, one which Green’s other, equally strange and scintillating, films confirm and extend.

Saturday, August 31, 2019

Black Jack (Ken Loach, 1979)

Black Jack has the trappings of a classic kids’ adventure yarn – a boy falls in with an escaped convict and embarks on an eventful odyssey including a spell with a traveling fair, a girl who escapes an intended fate in the madhouse, multiple blackmails and a mysterious death. It’s certainly something of an oddity in Ken Loach’s oeuvre, and the director apparently views it as a disappointment, hampered by budgetary and other production constraints. But the film’s sparseness, the sense of not being quite fully formed and articulated, actually constitutes its main appeal – there’s something perversely enjoyable about how the basic exposition has to fight against thick accents and mushy articulation (it feels just about perfectly cast, exactly because of the imperfections of its people). The film avoids scenic overkill while sustaining a grubbily painterly quality, and the attention to detail is impressive: I don’t recall ever seeing a period film where the clothes are so authentically frayed and worn. By Loach’s standards, the film isn’t particularly explicit perhaps in diagnosing the surrounding society, but that makes a point in itself: for example, about the looseness of governing structures that allow a girl’s liberty to be signed away on the whim of her parents (on the other hand, it does establish that a strong-willed teenage boy can accomplish a lot, for good or for bad). This leads to an unusual climax in which the truth about that mysterious death is discovered, but without any apparent thought that the perpetrator might be brought to justice. The film delivers a traditional flourish at the end, with boy and girl escaping off to sea (by that point, the eponymous Black Jack has long ceased to be at the heart of the narrative), but overall its stubborn integrity places it with Jacques Demy’s The Pied Piper among the stranger supposedly child-friendly creations.

Saturday, August 24, 2019

Docteur Popaul (Claude Chabrol, 1972)

Saturday, August 17, 2019

Claudine (John Berry, 1974)

For a mainstream (ish) romantic comedy, John Berry’s Claudine is remarkably short on sustained exuberance or joy; it’s suffused with the weight of getting by, the near-impossibility of making all the pieces add up. The movie’s early stages tease us with the prospect of a black story conducted in the margins of a white society, with Claudine’s employer looking on as she flirts with the ebullient garbage collector Roop. But welfare workers and cops aside, that’s as prominent as whiteness ever gets in the mix: from then on we’re embedded in black rhythms and attitudes and concerns, to an extent that still feels fresh and daring. She’s a single mother of six kids, getting by only by juggling those government handouts with off-the-books domestic work, living in a state of constant look-out for the unannounced visits that may bring the edifice crashing down. The movie presents it as a virtual social inevitability that a woman like Claudine will often be in the situation she’s in, and that a man like Roop will often be responsible for leaving women and kids elsewhere in parallel situations, but also understands why they’d still jump in again (it carries a discreet but unmissably raw sexual charge): the characters understand the cycle and pay a price for it, but can’t countenance the amazing radicalism of Claudine’s oldest son, who goes out and gets a preemptive vasectomy (an act that Claudine perceives as yielding power to the white man). The movie adheres to its genre to the extent that it culminates in a marriage, but the vows are barely spoken when turmoil and violence bursts in, leading to a very unusual end-credits image of familial unity. Diahnne Carroll wonderfully comveys both bone-tiredness and the spark that keeps her going, and James Earl Jones as Roop has seldom displayed such contrasting relish and vulnerability.

Saturday, August 10, 2019

Car Cemetery (Fernando Arrabal, 1983)

Saturday, August 3, 2019

Craig's Wife (Dorothy Arzner, 1936)

Dorothy Arzner’s Craig’s Wife is a potent, expertly (albeit melodramatically) condensed account of a woman’s unraveling, full of finely observed detail and broader social implication. John Boles’ Walter Craig lives almost solely for his wife Harriet, blind (to a perhaps somewhat improbable extent) to what everyone else sees as her calculating materialism and alienating coldness: when an elderly aunt finally lets fly with the truth, he initially can’t see it, but subsequent events involving a police investigation and a vague threat of scandal drive the point home, and thus bring everything down. Rosalind Russell doesn’t hold back on establishing Harriet’s unpleasantness, smugly setting out her philosophy of manipulation and dominance in an early scene, dismissing her younger niece’s arguments for romantic love: the film captures her obsessive observation and calculation, her eyes perpetually prowling over every inch of her domain, computing the implications of every small intrusion. But the film also acknowledges that the threat is real, that women (including Harriet’s own mother) are abandoned all the time when the men move on from them (the police-related subplot establishes that a woman who attempts to exercise the same self-determination as a man may pay with her life) and that for all her excesses, Harriet’s behaviour represents a rational (even if in this case misplayed) response to a stacked deck of a society. Harriet’s miscalculations cost her dearly, abandoned by everyone around her, even down to the servants, fulfilling the film’s closing maxim that those who live to themselves are generally left to themselves. Arzner’s magnificent handling of the final scene renders the previously showcase-like home suddenly overwhelming and unnatural, and Russell’s final close-up carries a sense of searching for divine intervention as she starts to realize her isolation, and therefore, perhaps (and depending on the viewer’s own social critique), a possibility of renewal.

Saturday, July 27, 2019

Insiang (Lino Brocka, 1976)

Saturday, July 20, 2019

Water (Dick Clement, 1985)

Sunday, July 14, 2019

Two People (Carl Dreyer, 1945)

Even allowing that Dreyer disowned Two People, it’s strange it receives quite so little attention in discussions of the director; it’s fascinating in its failure, feeling tonally and thematically linked to the two features he made subsequently. The film focuses on a young married couple under extreme strain: they’re the only faces we see, although there are other voices, and it’s set entirely in their apartment, although it evokes other spaces in various ways. Arne is an up and coming scientist who’s been publicly accused of plagiarizing an older professor (stealing his cure for schizophrenia, no less); in the midst of the (improbably headline-grabbing) scandal, the news comes that the professor has been murdered, with numerous clues pointing toward Arne as the perpetrator. Marianne tries to lend her support, but eventually reveals her own tangled involvement with the dead man. The narrative lurches around, cramming far too many reveals and reversals into its 70 minutes: it makes no sense that signposts of guilt keep flooding in from the outside world (for example, they learn from the radio that the police found a glove with Arne’s initials on it) while no one in authority comes to interview the couple, and yet this contributes to the sense of an intimately sealed-off world, bending external reality to its own precepts (tbe professor is heard only in a single flashback, and then seen only in shadow, as if harking back to Vampyr, and the lead actor’s occasional resemblance to Bela Lugosi inadvertently – presumably it was inadvertent - contributes to a sense of creepiness). In its ultimate capitulation to a transcendent love that justifies almost all, Two People looks ahead to Dreyer’s final film Gertrud, but the journey is inadequately articulated here, with the ending feeling more like an arbitrary twist than anything else. Stylistically though, the film often does feel close to Gertrud, carrying an air of devout, stark observance, and for all its manifesr weakness, it casts a strange if broken spell.

Sunday, June 30, 2019

Sapphire (Basil Dearden, 1959)

Saturday, June 29, 2019

Morel's Invention (Emidio Greco, 1974)

If one didn’t know Emidio Greco’s L’invenzione di Morel was based on a novel, it might easily be taken as a response to Tarkovsky’s then-recent Solaris – although not set in space, its isolated island setting amounts to much the same thing, and the plotlines are similar in their blurring of the line between humanity and illusion, and in the related capacity for cinematic metaphor. With tweaking and a much-souped-up visual style, Greco’s film could also feel like the forerunner of a Black Mirror installment. A man is washed up on the island, his boat wrecked beyond repair (there’s little backstory beyond a passing reference to political problems) – the island holds a large structure that’s part museum shell and part industrial complex but initially seems uninhabited, but then he starts to see people, dancing and conversing with little attention paid to their challenged surroundings, and with none at all paid to him (the most striking among them is played by Anna Karina, who even more than in most of her post-Godard work is utilized here as pure image). The film is strikingly composed and edited, often wordless for long stretches, at others dense with exposition and self-interpretation as the title’s Morel, gradually revealed as dominant among these dispossessed individuals, reveals his invention, and the place of the others within it. As noted, the film draws on a classic cinematic proposition, of the screen and the spectator’s submission to it as a rewriting of and usurpation of reality – in this respect, it necessarily belongs to a time of cinema as physical destination, long predating the tyranny of tiny screens. It’s not the most galvanizing of works – there’s no respect really in which Greco is as interesting as Tarkovsky, and the film does skirt turgidity at times – but it has an elemental enigmatic power, and deserves better than its substantially forgotten status (an ironic fate perhaps, given its premise).

Sunday, June 23, 2019

Machorka-Muff (Jean-Marie Straub and Daniele Huillet, 1963)

Straub and Huillet’s Machorka-Muff introduces itself, in an opening title signed just by Straub, as “an abstract visual poem, not a story,” which at once prepares the viewer for the narrative challenges of the following 18 minutes, while perhaps underpreparing him or her for its precision and tangibility. The film certainly has far more story than, say, a Stan Brakhage short: it contains both personal and professional development, it conveys a lot about character, it draws on an identifiable surrounding time and place, it has a beginning and middle and end, in that diegetic order. It even has a certain amount of dry, arch comedy, mostly based in the protagonist’s suffusing self-regard and unrepentant militarism. In all these respects it’s a remarkable feat of condensation, even making time for what may appear like digressions, such as the precious moments devoted to a waiter as he fills a drinks order. It perhaps feels least like a poem in its montage of (apparently genuine) newspaper headlines that advocate for German rearmament, drawing Jesus Christ into the cause and concluding by asking whether Germany will be a hammer or a nail, but at the same time this constitutes the most dramatic expansion of the filmic space. Viewed at a time when class-based expectation and division is only reasserting itself, and when post-war institutions are under escalating economic and political threat, the film feels like a warning, even a stern one, but it never feels confined by advocacy; the hard-edged specificity is always in conversation with the asserted abstraction, allowing the feeling of a film at once oppressive and yet strangely liberating. The final note, an assertion of embedded social power that no one’s ever dared to oppose, goes unanswered within the film, but sets a challenge for Straub-Huillet's ensuing body of work, with its emphasis on resistance and engagement.

Sunday, June 16, 2019

Mary Jane's Not a Virgin Anymore (Sarah Jacobson, 1996)

One’s reaction to Mary Jane’s Not a Virgin Anymore is inevitably conditioned by the knowledge that it was the only feature completed by Sarah Jacobson, who died a few years later of cancer at the age of just 32. I don’t think it’s only in hindsight that the film carries a sense of looming darkness – actually it’s explicit in the pervasive use of black backgrounds, often giving events a rather disembodied feel. It makes for peculiar viewing, given that in summary the film might sound well within a tradition of brightly raunchy sex comedies – Mary Jane unsatisfactorily loses her virginity (in a cemetery yet), triggering a heightened interest in her own sexuality and that of her circle of colleagues at the movie theatre where she works (the programming for which appears to be carried out in some underwhelming parallel universe), most of whom are older and worldlier than she is (much is made of her origin in the suburbs). The movie has a punk-infused feel, often feeling on the verge of tipping over into something more radically unbound (the acknowledgement in the end credits of “everyone who ever bought me a beer” is a nice touch), but remains primarily in investigative mode, accumulating something of a dossier of mixed-bag “first time” stories and gradually expanding its field of concern and awareness to encompass bisexuality, unplanned pregnancy, sudden tragedy, and more, ending (rather abruptly) on a note of self-determination and moral victory. Those closing credits roll over an extended rant into the camera by a disgruntled theatre patron, basically a verbal assault on just about everything, as if to emphasize the movie as an act of resistance. It’s more persuasive than not: it would be pointless to oversell the film’s impact, but when you reflect on the great careers that followed from comparably (or more) modest beginnings, the sense of loss is severe.

Sunday, June 9, 2019

The Soft Skin (Francois Truffaut, 1964)

Sunday, June 2, 2019

Room at the Top (Jack Clayton, 1959)

Jack Clayton’s Room at the Top feels distinctly overwrought now, with its nakedly ambitious protagonist Joe Lampton barely uttering a word in the early stretch that doesn’t relate to his calculated social-climbing, and then reduced to near-catatonic silence in the end as he achieves a version of his ambitions, at the cost of (at least temporarily) losing his soul. The notoriously problematic actor Laurence Harvey tacks too strongly into both states, eradicating much possibility of subtlety, but at least aiding the film’s harshly elemental impact (one of the film’s most effective elements is his unspoken realization that the wealthy girl of his dreams is, basically, unbearably boring). Despite these excesses, it remains a fascinating social document, depicting a society of painful limitations, consumed by self-defeating power games (one of the more striking scenes is that in which the husband of Lampton’s older lover confronts him, setting out with cold meticulousness why the affair has to end, the relish he takes in his victory far outweighing any remaining feeling for his wife). Certainly it’s not a world devoid of pleasures and camaraderies, but they depend on a benign acceptance of limits, a shutting of one’s mind to all vertical possibilities. Sex, of course, is the most prominent of the horizontal availabilities, fueling a significant hidden infrastructure and a network of behind-back conversations. Simone Signoret won an Oscar as the lover, but even the mild exoticism she brings to the film feels like more than the milieu deserves or can accommodate (albeit this is largely the point). Looked at now, it’s no doubt a museum piece on any levels, not least for the prominence of heavy manufacturing in the economic hierarchy. But while Britain may have given itself several coats of paint since then, the inequalities and abandonments have only become more savage, rendering the film’s moral contortions almost quaintly benign by comparison.

Sunday, May 26, 2019

The Touch (Ingmar Bergman, 1971)

Sunday, May 19, 2019

Scrubbers (Mai Zetterling, 1982)

Mai Zetterling’s Scrubbers certainly feels sociologically and humanly scrupulous, examining the fraught community within a female borstal while largely avoiding swaggering stereotypes and easy titillation.The recurring use of bawdy folk-type songs is just one suggestion that for all its forced unnaturalness, the world that the inmates craft for themselves may preserve English community and culture more fully than what lies outside – by comparison the portrayal of the staff is mostly clipped and sparing and deliberately disconnected. Zetterling seems most artistically stimulated by the environment’s inherent abstraction, triggering the film’s most unexpected impact, its outbursts of visionary Kubrick-like strangeness. That would be both Kubrick past (a dispossessed mother’s dreams of her kid might almost have slotted into The Shining) and even – relative to the film’s 1982 release date – Kubrick future: the prison might well share a designer and all-seeing cinema-eye with the dorms of Full Metal Jacket. Just as in Jacket, the rituals and tasks (such as assembling cheap plastic dolls) of the institution barely contemplate the chaos of the real world battle to come - the institution seems in no way to provide a meaningful response to the transgressions of its two main protagonists (one can only think of being reunited with her infant daughter; the other was motivated primarily by apparently unrequited love for another inmate), whether as punishment or rehabilitation (a more conventional but still well-handled vignette has one of the tougher inmates released into a world for which she’s entirely unprepared). It follows that the film withholds any kind of closure, leaving the prospects of its key characters uncertain after a final disorientating plunge into the outside world, ending on a recurring exterior nighttime shot that eavesdrops on the inmates as they yell out their goodnights and other parting shots for the day. This device may seem to evoke The Waltons of all things, but it’s certain that nothing else in the movie will.

Sunday, May 12, 2019

Mille milliards de dollars (Henri Verneuil, 1982)

Sunday, May 5, 2019

The Coca-Cola Kid (Dusan Makavejev, 1985)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)