Watching Donald Cammell’s White of the Eye, your mind oscillates between wanting to dismiss it as essentially dismal I-married-a-serial-killer stuff, and constant wonderment at how Cammell ventilates and expands every aspect of it, generating a movie that feels at once frostily deadened and almost Messianically possessed. David Keith plays Paul White, a hilariously bland label for a character depicted as hypernaturally connected, carrying out his work as an installer of high-end audio equipment as much through heightened senses as technical expertise, a proficient hunter (until his wife Joan made him give it up, sort of) coded through various Native American appropriations. He met Joan (Cathy Moriarty) when she was passing through his hometown of Glory, Arizona with Mike, a boyfriend, on the way to Malibu – she never made it out of Glory, and a decade or so later, she finds that Mike is also back there, mentally diminished after an accident while serving time in New York. Paul comes under suspicion in a string of killings, and for a while it seems like a classic wrong-man set-up, until Joan finds something, and he turns on a dime, rapidly shedding every element of established personality and morality, becoming something close to sheer abstract threat (the corresponding swerve in Keith’s performance is no less startling). The endgame has Mike improbably showing up in the middle of nowhere at the right time – a tired narrative device converted here into something expansively formative (with a homoerotic undertone), as if we’ve been watching the culmination of God’s own plan. Almost every scene makes a mark of some sort, whether through oddity of character, flamboyance of design, or sheer penetrating strangeness, and if one often feels that Cammell should have managed bigger and better films, the film almost seems to be embracing displaced self-destructiveness at its heart, and daring people to find it lacking.

Friday, April 24, 2020

White of the Eye (Donald Cammell, 1987)

Watching Donald Cammell’s White of the Eye, your mind oscillates between wanting to dismiss it as essentially dismal I-married-a-serial-killer stuff, and constant wonderment at how Cammell ventilates and expands every aspect of it, generating a movie that feels at once frostily deadened and almost Messianically possessed. David Keith plays Paul White, a hilariously bland label for a character depicted as hypernaturally connected, carrying out his work as an installer of high-end audio equipment as much through heightened senses as technical expertise, a proficient hunter (until his wife Joan made him give it up, sort of) coded through various Native American appropriations. He met Joan (Cathy Moriarty) when she was passing through his hometown of Glory, Arizona with Mike, a boyfriend, on the way to Malibu – she never made it out of Glory, and a decade or so later, she finds that Mike is also back there, mentally diminished after an accident while serving time in New York. Paul comes under suspicion in a string of killings, and for a while it seems like a classic wrong-man set-up, until Joan finds something, and he turns on a dime, rapidly shedding every element of established personality and morality, becoming something close to sheer abstract threat (the corresponding swerve in Keith’s performance is no less startling). The endgame has Mike improbably showing up in the middle of nowhere at the right time – a tired narrative device converted here into something expansively formative (with a homoerotic undertone), as if we’ve been watching the culmination of God’s own plan. Almost every scene makes a mark of some sort, whether through oddity of character, flamboyance of design, or sheer penetrating strangeness, and if one often feels that Cammell should have managed bigger and better films, the film almost seems to be embracing displaced self-destructiveness at its heart, and daring people to find it lacking.

Friday, April 17, 2020

The Nun (Jacques Rivette, 1966)

Although Jacques Rivette’s La religieuse focuses on a young nun fighting for her freedom, the film never seems to discount the possibility of devotion and God’s grace: the outrage lies in using religious institutions as a means of social control. The protagonist, Susanne, is pushed by her family into taking her vows because of financial and social considerations, the France of the time (around 1750) apparently allowing no practical alternative that they can perceive or tolerate: the bulk of the narrative follows her mistreatment at the hands of one vengeful superior, and her attempts to avoid the desirous advances of another. The film is most audacious in its final stretch, after she escapes with the assistance of an equally unhappy priest: it skips through subsequent events (perpetually in fear of being recaptured; reduced either to begging or else working in a series of menial or demeaning jobs) in fragmented fashion, suggesting that for all her unhappiness, the institution did provide a form of coherence that the outside world lacks. Of course, this only underlines the pervasive lack of alternatives for a woman who falls outside the prevailing structures of control and belief. Anna Karina is a perfect centre for the film, entirely convincing and moving in her essential goodness, driven not by inherent rebelliousness but by a sense of wrongness, that God sees through and is offended by her pretense, even as many of those around her offend against their vows in different ways. It’s hard to know how easily a viewer could attribute the film to Rivette, if he or she didn’t already know it's his, but among other things, the film evidences his affinity for theatre and performance, as for instance in the opening scene where she takes her vows before an audience, separated by a grill, and more broadly in the notion of God as the ultimate perceived spectator and judge of authenticity.

Friday, April 10, 2020

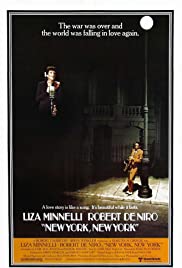

New York, New York (Martin Scorsese, 1977)

Martin Scorsese’s New York, New York is one of his most fascinatingly strange films, a meeting of varied artifices and evasions. Robert De Niro is Jimmy Doyle, a virtuoso saxophone player who resists the confines of the prevailing post-war swing band aesthetic, drawn to more experimental, improvisatory forms; Liza Minnelli is Francine Evans, a singer of more traditional instincts: their incredibly volatile relationship reflects the tensions of diverging desires and ambitions (they meet in the thick of VJ Day celebrations, placing the film in part as a parable of post-war reconstruction). Within the decade or so of the (deceptively conventional sounding) plot, Francine ends up as the bigger star, with a Hollywood and nightclub career that looks much like that of Minnelli’s mother Judy Garland; the film doesn’t emphasize what every viewer knows, that the mainstream will soon leave her behind (Minnelli herself was already at the end of her brief movie-starring heyday). De Niro’s performance is among his most extreme, a barrage of challenges and provocations (Jimmy’s treatment of Francine certainly constitutes some kind of abuse) that doesn’t feel like old Hollywood, but which is too stylized to fit comfortably into the new: coupled with the frequent artificiality of the film’s backdrops, it often feels like pure abstracted challenge. It’s grandly appropriate them that the last stretch of the film consists almost entirely of performances, primarily by Francine (and all absolute Minnelli classics), with her and Jimmy’s personal story coming to be defined by inarticulacy and absence (with echoes of Antonioni’s The Eclipse). Even before that, the movie has several moments that almost seem to pause, to separately observe Francine and Jimmy at moments of silent contemplation, as if insisting that it’s interested in inner lives, even as it represents an America steadily progressing deeper into obsession with image and projection.

Saturday, April 4, 2020

Mexican Bus Ride (Luis Bunuel, 1952)

Luis Bunuel was already in his early fifties when he made Mexican Bus Ride, and one can imagine an alternative history in which it would have been a sign of winding down, of easing into dawdling conviviality of the sort that characterizes the titular journey: the bus only gets going when it’s full, adhering to no fixed schedule – progress gets interrupted along the way by a flat tire, by being stuck in mud, by a woman giving birth, by driver fatigue, and finally by a detour to a birthday celebration. A bit of frustration gets expressed at all this, but for the most part the passengers take it in stride, the journey being as important as the destination, and efficiency being a rather suspect commodity (during the mudbound episode, a pair of oxen acquit themselves much more effectively than a modern tractor). The passenger at the centre of our attention is Oliverio, heading to find and bring back a lawyer to document his dying mother’s will, knowing that otherwise his scheming older brothers will manipulate her for their own self-interests – the urgency of the situation pulls him away from his wedding night, and exposes him to the relentless advances of a female passenger (to whom he seems to represent a pure sexual itch that she’s determined to scratch). A few sharp Bunuelian strokes dispel any potential sense of complacency: a vividly imagined dream sequence drawing on Oliverio’s faltering resistance to temptation; a willing no-strings-attached consummation in the midst of a storm; and a final few scenes in which he arrives back too late, but forges his mother’s mark on some documents for the sake of implementing her expressed wishes, before drawing his wife close and uttering a fiery statement of intent. The movie’s positioning of adultery as a galvanizing force and of manipulation of the dead as a morally righteous act still feels defiantly transgressive, a sign of a filmmaker with a startling journey still ahead.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)