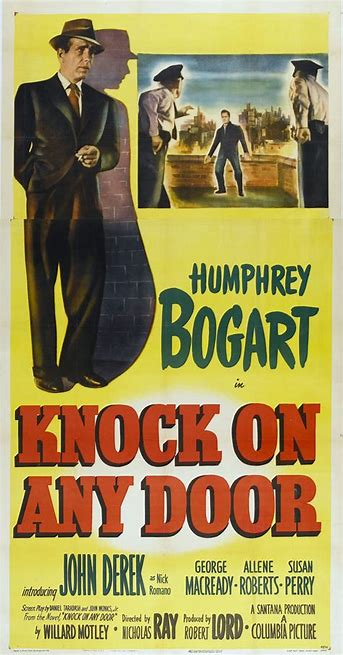

In Nicholas Ray’s Knock on Any Door, commercial attorney Andrew Morton (Humphrey Bogart) steps back into his criminal-law past to defend Nick Romano (John Derek), a young “hoodlum” accused of killing a police officer: much of the first half unfolds in flashback as Morton recounts for the jury his past experiences with Romano, and his own possible partial culpability for why the young man’s life went wrong; the second half focuses mainly on the trial itself. The rather ungainly structure and all that’s packed into it generates a feeling of Ray being hemmed in much of the time, finding limited room for visual invention or meaningful character exploration; it achieves a few grace notes at the end though, in a lonely overhead framing of Morton making his final argument, and in the very final, transcendence-tinged shot (no less striking for being rather absurd). John Derek’s Nick Romano is as thin a presence as everyone has always said, but Bogart is as fascinatingly shaded as always, and the diverse supporting cast accommodates Preston Sturges-like eccentricity, unrestrained excess, wild intensity, the soft-spoken loveliness of Allene Roberts as the girl with whom Romano falls in love, and a relatively prominent, naturalistic Black character, whose testimony sparks a courtroom blow-up over whether or not he would even have been allowed inside the bar where he claimed to be at the time of the murder. The film’s speechifying, however overdone, still connects at a time when large factions of mainstream America seem to be defined largely by drummed-up fear and paranoia; the revelation that Romano is actually guilty, despite Morton’s skilled argument for his innocence, speaks directly to the wearisome burden of maintaining one’s idealism. But overall, it’s instructive that a film so strenuously seeking to enhance our sense of ambiguity and perspective should end up being one of Ray’s most unilluminatingly straightforward.

Tuesday, April 25, 2023

Tuesday, April 18, 2023

The Beekeeper (Theo Angelopoulos, 1986)

Theo Angelopoulos’s

The Beekeeper feels rather strenuous at times, but it’s a quality rooted

in bottomlessly searching despair, for its central character and the world he

represents, and for the fate of the mode of cinema in which such an individual could

be the protagonist. Marcello Mastroianni (inherently deep in art cinema

resonance, but cast here in sternly withholding mode) plays Spyros, newly-retired

from his small-town schoolteacher position, attending his youngest daughter’s

wedding and then leaving behind his family (which in any event seems to be

barely held together) to focus on his beekeeping, depicted here as a nomadic vocation,

driving from one location to another, setting up and tending the hives for a while

and then packing it all up and moving on; along the way he gives a ride to a

young, unnamed woman, and their paths keep crossing thereafter, her attitude

toward him ranging from affectionate to contemptuous, sometimes almost simultaneously.

The film’s effective climax could hardly be more symbolic: Spyros and the woman

spend the night in a disused cinema likely slated for demolition, where she

undresses before him as if in sexual offering, but the resulting contact is

bizarre and suffused in alienation, apparently marking the end of the dance

between them; from there it’s a short journey to an final scene in which Spyros

reaches his tragic existential destination, powerfully conceived and haunting, but

less for an individual man’s fate than for that of a generation, its collective

memories, its relationship to homeland and tradition. Much of the film might

have been set decades ago; the film’s newest-looking locations are also among

its most desolately alienating (in this context, a passing reference to Dire

Straits’ Brothers in Arms seems weirdly out of place), defined by almost

empty, characterless roadside diners and the like, and by numerous shots of people

moving in expressionless, almost zombie-like manner.

Thursday, April 13, 2023

Les stances a Sophie (Moshe Mizrahi, 1971)

Moshe Mizrahi’s Les stances a Sophie

falls a little short of feminist classic status, but it’s a spikily enjoyable work

from start to finish, excellently drawing on Bernadette Lafont’s distinctive crossing

of slightly removed amusement with unerring seriousness of purpose. She plays Celine,

a low-overhead arty type, who in the film’s opening stretch meets and sort of

falls for businessman Philippe, accepting his marriage proposal in part because

of what she calls “gravitation.” She’s hardly suited to the world he inhabits (a

scene early in their marriage has him trying to drum the details of the coming evening’s

social commitment into her head while she’s entirely preoccupied with trying to

remember the previous night’s dream), but benefits from her friendship with Julia

(Bulle Ogier), wife of Philippe’s best friend Jean-Pierre, who shows her some

of the rich woman ropes (which, in one of the film’s less progressive notions, largely

seem to involve buying clothes); in turn, Celine’s greater appetite for sex

seems to help Julia out of her “semi-frigid” state, and the two eventually start

collaborating on a theory-informed study of gender relations. But the film thwarts

any expectations of a sexual free-for-all: in particular, Celine’s response to

a pass that Philippe makes on her is withering, and the exact nature of her close

relationship with Philippe’s sister is left unclear. Mizrahi has some fun with masculine

car obsessions and their dim view of female drivers, until the joke turns

bitterly sour, leading to an ending that delivers the expected note of

liberation and self-determination while weaving in some intriguing notes of

regret, abiding affection and male desolation. The film’s reputation is much bolstered

(in some quarters entirely constituted by) the score by The Art Ensemble of

Chicago, its only such feature-length assignment; their work soars and pivots

and counterpoints, bolstering the sense of investigative complexity.

Wednesday, April 5, 2023

Under the Blossoming Cherry Trees (Masahiro Shinoda, 1976)

The title of Masahiro Shinoda’s Under

the Blossoming Cherry Trees seems to promise a largely soothing experience,

and even after the warning in an opening voice over that such trees were

historically more to be feared than relished, it still often seems possible

that the film might ultimately find its way into such a register. But that’s just

one aspect of its continual capacity to surprise and misdirect, being at various

other times blackly comic, cartoonishly violent, mythically possessed, or (in

the extended relish with which it plunges into urban hustle and bustle) an

amused study of the gap between city and country. Ultimately this might all be

tied together as an extreme parable on the perils of getting what you wish for,

built around a mountain-dwelling bandit in ancient Japan who slaughters a group

of travelers from the city, sparing a woman he finds uniquely beautiful and

decreeing she’s to be his wife. The captive accepts her fate with strange

equanimity, while harassing him from the start and testing him with extreme demands,

including that he kill most of the multiple women he already has on hand;

eventually she persuades him to move to the city, where he slaughters dozens of

victims for the sake of feeding her growing obsession with disembodied heads. But

it’s hardly a sustainable way of life, and in the end they set off back to the

country, his excitement at going home causing him to disregard his usual

caution regarding the cherry trees, and their fate accordingly awaits them.

It’s a visually striking ending, but also an evasive one, potentially leaving

the viewer feeling rather abandoned. But then there’s a final shot of the trees,

certainly looping back to that opening warning, and perhaps commenting more

generally on how our modern-day traditions and rituals lack a sense of the past

complexity and turbulence from which they arose.