Wednesday, August 25, 2021

Into the Night (John Landis, 1985)

Wednesday, August 18, 2021

Jeanne La Pucelle: Les Batailles (Jacques Rivette, 1994)

As superbly realized by Jacques Rivette,

Jeanne d’Arc is both a figure of immense psychological and historical

specificity, and a forerunner of the kind of behavioural mystery that populates

much of his great contemporary-set work. The mystery of how an illiterate young

woman could have acquired such vision and purpose is integral to her longevity

as a cinematic icon, and Rivette allows room for a range of readings and

responses; for example, she convinces the “Dauphin”, whom she aspires to restore

to the throne, of her legitimacy by privately revealing something to him that

(in his words) only God would know, but the film withholds the details of what

that actually consists of. Sandrine Bonnaire perfectly embodies Jeanne’s

stubborn fortitude, while also conveying her fragility and immaturity, her

feelings easily hurt by enemy insults, entirely believable when she says she

would rather have been at home sewing; the physical immediacy of her presence

channels that of the film around her - the climactic battle scene captures as

few others ever have the sheer smallness and intimacy of war at that time, the primitiveness

of the weapons and tools at hand, the physical closeness between adversaries, the

overwhelming fatigue. This vividness meshes with Rivette’s recurring interest

in theatre and performance, with Jeanne clearly aware of herself as a

projection, styled and dressed to fit the desired image, keenly aware of the power

of symbolism in forging reality (such as her insistence in using that term “Dauphin”

until the circumstances justify its replacement by “King.”) For all its

seriousness though, the film isn’t without a streak of deadpan socially-based

comedy, particularly in the varied reactions of the male soldiers to the

impassioned female in their midst (she instructs one of them in toning down what

she sees as his overly colourful use of expletives).

Thursday, August 12, 2021

The Spy who Came in from the Cold (Martin Ritt, 1965)

A film like Martin Ritt’s The Spy who Came in from the Cold takes on an additionally bleak resonance in the post-Trump presidency period, where every day provides added evidence of how easily principle is abandoned, corruption is embraced, and black is proclaimed as white: one major difference is that whereas Ritt’s film describes a world of grubby little men mostly operating in shabby circumstances, our modern day schemers and traitors stand proudly under the coldly facilitating lights of social media. Without such present-day reference points, such cold war films might increasingly seem to retreat into pure dated abstraction, endless games of positioning in which the assessment of political (let alone moral) ground won versus lost becomes impossibly rarified and subjective. Spy who Came in from the Cold – revolving around a field officer now (apparently) out of the game, his personal weaknesses perhaps driving him to flirt with treachery - remains one of the more compelling examples of the genre, not least for the wondrously drab depiction of working-class Britain, with several references to the low wages for which people toil away, and an almost total absence of any sense of pleasure and fulfilment beyond what alcohol provides, all of which squashes any sense of ideological idealism; indeed, the most biting enmity in the film is between an ex-Nazi and a Jew who now find themselves (officially at least) on the same side, old prejudices and resentments at best only temporarily suspended. For all the film’s condensed and stylized aspects, it conveys a compelling sense of pervasive societal unease and insecurity, capable of pushing people toward extreme action, even if they could hardly explain the specific logic of those actions. Richard Burton, seldom an ideal film actor, is at his most effective here, his stiffness befitting a character consumed by self-loathing and cynicism.

Wednesday, August 4, 2021

Un jeu brutal (Jean-Claude Brisseau, 1983)

The title of Jean-Claude Brisseau’s Un jeu brutal might

refer both to the specific contrivance that’s ultimately revealed to drive the

plot, and to the all-embracing, terrible wonder of creation – it’s a measure of

Brisseau’s conviction, his odd brand of depraved poetry, that the duality

doesn’t seem merely pretentious. Christian Tessier (Bruno Cremer) is a

brilliant scientist who quits his role in cancer research (sacrificing potential

saviour-status when his former colleagues shortly afterwards announce a

breakthrough) and returns to live with his teenaged daughter Isabelle (a

memorable Emmanuelle Debever), in whom he’s shown no interest for years; she’s

paralyzed in both legs, her behaviour almost feral, and he imposes a new regime

of order and education on her life, the faltering progress of which accelerates

after she becomes more sexually aware (by virtue of secretly observing her

young female teacher lounging naked in her room, and later through her

partially reciprocated attraction to the teacher’s visiting brother).

Meanwhile, on his frequent trips away, Tessier is carrying out a parallel

project of slaughtering children, in what he ultimately reveals as a plan

ordained (in improbable coded message form) by God. The film frequently pushes

us to reflect on the cruelty of the natural order, and while Tessier clamps

down on Isabelle’s nastiness to animals and lack of empathy, the object appears

to be to harness and direct the darkness of one’s nature rather than to suppress

it, for the purpose of more fully emerging into the light – Brisseau frequently

bathes in the varied beauty of the landscapes around the house, from field to

river to mountain, with individual scenes evoking concepts of baptism, or

pilgrimage, or rebirth. It would be a stretch to call the film entirely admirable

or credible, but it may linger in the mind longer than many more

straightforwardly consideration-worthy works.

Wednesday, July 28, 2021

The Brave (Johnny Depp, 1997)

Seen in retrospect, Johnny Depp’s The

Brave (made when the actor was just about at his peak of coolness, preceding the

commercial highs to come and the subsequent reputational collapse) seems suffused

by a desire to withdraw – into silence (there’s little dialogue, and none at

all for the first ten minutes or so), into myth and beyond. The film is set around

a hand-to-mouth melting-pot community, the landscape dominated by mounds of

garbage and shimmering heatscapes, which suddenly yield to something

quasi-Lynchian as Depp’s unemployed and luckless Raphael, following on a tip he

received in a bar, enters a strange building to ask about a job, descending

into a symbolic hell in which he’s eventually offered $50,000 to extinguish

himself in a snuff film in a week's time. Taking the offer and a cash advance on the basis of

stunningly little negotiation, Raphael conspicuously spreads the money around,

attracting various kinds of suspicion; at the end of the week, he’s strengthened

his core spiritual bonds, while putting himself beyond redemption in other

ways. The film resists the audience’s most likely expectations, whether for

some kind of last-minute escape or for any depiction of what Raphael must finally endure; with

his business with the world as we know it concluded, it leaves his final hell

to him and his acquirers. Depp has an intriguing if patchy feeling for

eccentricity, although it’s a rather distant viewing experience, even allowing

that this is inherent to what’s intended. The film has at least one major see-it-if-you-can

aspect, the casting of a long-haired Marlon Brando in one of his last roles,

extending the fateful offer from a wheelchair, in between musing on pain as a virtuous

end to life and blowing on a harmonica, a performance no doubt “phoned in” by some

measures, and yet embodying Brando’s unmatched capacity to transform whatever

cinematic space he (however peculiarly) chose to occupy.

Thursday, July 22, 2021

Plaisir d'amour (Nelly Kaplan, 1991)

Nelly Kaplan’s last feature film, Plaisir d’amour,

works an enjoyable if not ultimately too surprising variation on a

self-gratifying male fantasy. Guillaume (Pierre Arditi), a practiced seducer

(1,003 past conquests, we’re informed), chances into a position as tutor to a

teenage girl on a tropical island; the girl is absent when he arrives, but

while waiting for her arrival he separately beds, with little difficulty, her

grandmother, mother and sister, all of whom share an elegantly dilapidated

colonial mansion, with no male authority figure in sight. He figures he’ll step

into the driver’s seat, but his attempts to impose greater order and efficiency

get nowhere, and he becomes obsessed with the perpetually delayed girl (whose

letters home and readily accessible diary indicates a psyche of a sexual

rapaciousness that outdoes his own). The film suggests greater moral stakes

through glimpses of fighting between the island’s army and its rebel faction,

and through its late 1930’s setting, with WW2 percolating in the distance; and steadily

muddies the sexual waters (both the women’s eccentric servant (Heinz Bennent)

and their talking parrot appear to regard Guillaume as an object of desire);

frequent references to Albert Einstein and a fanciful opening sequence throw in

some scientific and mystical resonances as well. In the closing stretch, it

becomes clear how little power and agency Guillaume has had throughout – he tips

over into quasi-madness, and becomes a simple nuisance, his utility spent. It’s

in no way a major film (not the equal of Kaplan’s La fiancée du pirate, which is much more zestily provocative on its own

terms, and more broadly resonant as a social critique), but it’s an

elegant one, even if a lot of it plays very conventionally and decoratively

(there’s seldom a moment when any of the women seem to be behaving entirely

naturally, albeit that this fits in with the artificially heightened nature of

things).

Thursday, July 15, 2021

The Solid Gold Cadillac (Richard Quine, 1956)

For all its contrivances and simplifications, Richard Quine’s The Solid Gold Cadillac is notable as one of the few movies about shareholder democracy, its uplifting finale revolving around the collection of sufficient small-stake proxy voting forms to overturn the complacent status quo. Laura Partridge (Judy Holliday), on the basis of her meagre holding of ten shares, regularly attends the meetings of the mighty corporation International Projects, irritating the complacent board members with her probing questions about their compensation packages and the like; they eventually give her a job, on the theory that it’s the best way to stifle her, but her threat to the established order only grows, especially when she starts a relationship with the company’s ousted founder McKeever (Paul Douglas), now in a high-ranking but unsatisfying Washington position. The film unnecessarily blunts its attack by, among other things, portraying the directors as such inept, disengaged boobs that they couldn’t possibly have attained such power (their sole plan to increase profitability is to get more government contracts, for which their strategy seems to consist solely of endlessly begging McKeever for them). The titular automobile only appears in the very last scene, as a symbol of Partridge’s ultimate professional and romantic triumph - the film switches from black and white to colour to better showcase the vehicle’s stunningness, although it’s rather a shame that a film that holds up corporate integrity and ethics would end on such a grandiose symbol of conspicuous consumption. For all the dismal personal behaviour on display, the movie is likely to be watched now with a significant amount of nostalgia, for a time when bloated dreams of self-enrichment capped out at annual salaries of a few hundred thousand dollars, or when an insignificant stakeholder like Partridge could even grab as much of the executive suite’s attention as she does here.

Wednesday, July 7, 2021

Rendezvous in Paris (Eric Rohmer, 1995)

Eric Rohmer’s Rendezvous

in Paris could almost evoke a rather plaintive response – the work of a man

in his mid-70’s, immersing himself in protagonists four or five decades younger,

obsessively examining and reexamining the mechanics of love and attraction, as

if in search of something that tragically got away. The film’s sparseness – it

was made under extremely minimal conditions, with just a handful of closing technical

credits – gives it the sense of a modern pilgrimage of sorts, albeit that the

site of the pilgrimage is on the doorstep, the city of Love, inexhaustible

fount of pleasure, frustration and complexity. The film’s three segments are

all, in the broadest sense, triangles: Esther suspects that her boyfriend

Horace is seeing someone else, and then by chance meets the someone else in

question; an unnamed woman, her relationship with her long-time partner on the

rocks, meets an unnamed man in a series of locations, unwilling to take things

beyond a certain level; a painter is set up with a Swedish visitor and takes

her to the Picasso museum, but then finds his attention drawn to someone else,

ending up without either woman. Rohmer’s genius with such material lies in his

extreme attention to detail and awareness of contingency, for example of how

the slightest change in the existing dynamic or equilibrium might disrupt

something that might otherwise have tenuously held together; the film’s final

scene points to how one never knows what may live in the memory, or may count

as a compensation. Regardless that the characters are mostly living fairly

basic lives, financially speaking, it’s hard not to view the film as a kind of

aspirational fantasy, in which disappointments and compromises are as

intoxicatingly necessary as the moments of fulfilment, all of it a reason to

keep walking and talking and flirting, and ending things and beginning others.

Wednesday, June 30, 2021

The Friends of Eddie Coyle (Peter Yates, 1973)

The title of Peter Yates’ The Friends of

Eddie Coyle subtly points to the film's structuring displacement – it identifies Eddie as its central point, played by its biggest star by far

(Robert Mitchum), but concerns itself as much with the chains of connection

around him, to the point that Eddie ultimately becomes more notable as absence

than presence. He’s a habitual criminal, looking to avoid pending prison time, even

at the cost of giving people up to the police – first the ones he doesn’t care

about, and then even those he does - but his view of the big picture, and of his

own place within it, is fatally limited. The film is populated with risk-aware characters

trying to shore up their positions, posturing and pushing others around, but often

still misjudging the real threats – it’s full of subtly tragic ironies and

inter-dependencies. But if the constant transacting of guns and information

almost verges at times on self-contained abstraction, the film provides

sufficient evidence of the brutal tangibility with which this activity intersects with the

real world, depicting a series of bank robberies (carried out with guns

channeled through Eddie) in forensic detail. The film’s audaciously desolate climactic

stretch has Eddie failing in his final play, and gradually fading from the

movie and from life itself, becoming drunk and incoherent and lost in a hockey

game crowd, his subsequent death shown with chilling offhandedness, treated

largely just as a training exercise between experienced and novice killers; in

the final low-key scene between two of those “friends,” his death is barely even

worth dwelling on. Mitchum is ideally cast, allowed a rare opportunity to evoke

a life and a history that don't run out at the edges of the frame, his wife

and kids briefly but astutely depicted, marooned outside the community of

“friends” that wearily propels his fate.

Thursday, June 24, 2021

A bout de souffle (Jean-Luc Godard, 1960)

It’s hopeless at

this point to try saying anything new about Godard’s Breathless, and yet of all

films it still feels like the one that might most be written about, or rather

responded to, whether in words or celluloid or gestures or dreams, still in

possession of a space all its own, where established orders of classical cinema

and post-war American exceptionalism and gender relations and social

correctness are in their different ways teetering or fraying or morphing, to be

abandoned or appropriated depending on their adaptability. One could rhapsodize

over every moment, but the dying run of Jean-Paul Belmondo’s Michel is as worth

singling out as any – a defiantly absurd cinematic flourish, but with real life

(or “real life”) all too

obviously continuing on each side of the street, people going about their business

apparently oblivious to, or unmoved by, the

gorgeous history-making charade taking place within feet of them, and yet

preserved for posterity whether they know it or

not, a moment of their life rendered transcendent even as they looked the other

way. One could speak of so much of the movie in similar terms – it shimmers

with a constant sense of delighted experimentation, of trying poses and

attitudes on for size, of relishing the sound of new words and the look of new

faces, of creating and immediately fully occupying fresh cinematic space, of

happy accidents (the resonances attaching to Jean Seberg prime among them). One

almost feels protective of her and the movie, knowing that Godard would so

quickly move on – for all Michel’s immense charisma (and Belmondo here is one

of the all-time great alluring screen presences, and he and Seberg one of

cinema’s all-time fascinating couples), he expresses himself worn out by the

film’s end, ready to yield if circumstances would have allowed (if a friend

hadn’t thrown him a gun), a capitulation that seems like Godard’s own

acknowledgement of territory already defined and conquered.

Thursday, June 17, 2021

The Unforgiven (John Huston, 1960)

John Huston’s The Unforgiven provides

some early images of pure relish, the three frontier-dwelling Zachary brothers

high on the imminent prospect of material wealth, with several references to the

sexual gratification that might follow, dynastically plotting to cement through

several possible variations of inter-marriage their ties with the neighboring

Rawlins clan. The fourth Zachary sibling, adopted daughter Rachel, seems in her

impulsiveness and vibrancy both more modern and more primal than the others, a

duality that becomes suspicious to the surrounding settler community when a mysterious

old man claims that her ancestry is Native American (in the film’s terminology,

Kiowa Indian); once the word is out, the Kiowa steps up its hostility and the community

starts to fracture from fear, suspicion and prejudice. In the end, the four

siblings are left standing among the ruins of their home and business, the

family’s coherence apparently having survived the ordeal, but the movie provides

little scope for optimism about its prospects of recovering its external bonds

and standing, or about those of the country being built around them. Huston’s delighted

engagement with actors reaches a kind of zenith here, pushing Audrey Hepburn

and Burt Lancaster to the point of frenzied excess at times, and surely

enjoying the contrast with Lillian Gish as the mother, a portrait in severe

perseverance; it’s Gish who’s at the centre of some of the film’s most haunting

(and we’re encouraged at times to read events in almost supernatural terms, as

if the layers of myths and past traumas standing in the way of progress were

ever lurking in spectral form) moments, playing on a grand piano out in the

open to counter the ominous music coming from their adversaries, or unilaterally

ending an in-progress “trial” by shoving the horse away, ensuring that the

defendant will end up hanging from the noose, uttering no more truth nor lies.

Thursday, June 10, 2021

The Holy Mountain (Alejandro Jodorowsky, 1973)

Watched shortly after the welcome ending of the Trump years,

the most prominent topical reference point for Jodorowsky’s The Holy

Mountain might be Qanon, a swirling, ever-renewing theory of everything, in

which its adherents claim (however sad their disillusionment) to transcend the

lying confines of conventional understanding (the main narrative follows a

group of powerful individuals, each associated with one of the planets, that

comes together to acquire ultimate power). Of course, the comparison is unfair

to the ecstatic and (in their way) deeply-sourced aspects of Jodorowsky’s work,

but the film is, by some measures at least, so (as they say) out there that it’s

hard for the uneducated viewer to separate meaning from opportunism. It

certainly impresses as an exercise in physically committed movie-making – pressing

tigers and hippos into action for the sake of one or two shots, marshaling a series of staggering crowd scenes, a parade of amazing sets and other design

elements and any number of logistically impressive shots (it’s staggering that

the budget was apparently under $1 million); it also has a constant parade of

nudity, mostly of an impersonally ceremonial kind of nature, summing up the

absence of much that feels authentically human, or relevantly rooted in

contemporary experience (leaving aside its various satirical aspects, for

example its parodies of the excesses of the military-industrial complex, which

although overdone at least further demonstrate the scope of Jodorowsky’s

imagination). The surprisingly offhand nature of the ending seems on the one hand

unequal to the involved quest that led up to it, but on the other hand asserts the

film’s most direct connection with its audience, an implicit invitation to take

from it what we wish and discard the rest. Still, even though one could list

the movie’s points of interest almost indefinitely, it all ultimately feels

less illuminating or potentially transformative than any number of far more

modest, earthbound works.

Wednesday, June 2, 2021

Airport (George Seaton, 1970)

George Seaton’s Airport is a pretty damn

irresistible entertainment machine, a portrait of society strewn with personal

failure and dissatisfaction, the trajectory of which is nevertheless toward

exceptionalism. It anticipates the present-day decline of American infrastructure

in how its Lincoln Airport is governed by low-vision local politicians more worried

about local interests and short-term cost considerations than looking ahead to

the future; the more far-sighted general manager Mel Bakersfeld (Burt

Lancaster) is the emblematic figurehead whom everyone both relies upon and

second-guesses. Bakersfeld specifically refers to himself as a kind of bigamist,

the first and official family all but broken and the second consisting of his

work; other main characters manifest similar tensions, home life coming second

to lovers, or blocked runways, or unattainable goals, reaching its apex in Van

Heflin’s Guerrero, overwhelmed by psychological and economical problems, evolving

the desperate plan to blow himself up on an aircraft so his wife might at least

reap an insurance windfall; the final scene of his wife (Maureen Stapleton), consumed

by unprocessable shame, may provide the film’s most raw, uncontainable emotion.

At the end of the day, the narrative resolves the most immediate problems with

a relative lack of grandstanding, and while the film is hardly a character

study, it has a somewhat greater interest in its people, even at their most

briefly-glimpsed, than the genre typically demonstrates. The dialogue

frequently emphasizes airplane durability and capacity (Boeing even receives a

specific grateful shout-out), radiating little doubt that even the most lurid

rupture will be purged (perhaps literally by being sucked out into space) and

that equilibrium will be restored, even if that may entail some reshuffling of

domestic arrangements. Among the relish-inducing cast, Oscar-winning Helen Hayes

is less the draw now than Jean Seberg, in her most prominent late movie,

embodying a model of supportive professionalism, her complex personal resonances

in no way drawn upon.

Wednesday, May 26, 2021

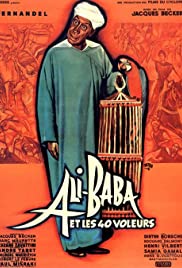

Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves (Jacques Becker, 1954)

Looked at through modern eyes, Jacques Becker’s Ali Baba

and the Forty Thieves is something of a moral atrocity – a plot driven substantially

by slavery and exploitation, set in a world where the ruling class appear to

admit no challenge to their hegemony, and in which women have no rights other

than what relatively benevolent men might gift to them. Ali Baba is sent by his

master Cassim to buy a suitable woman to add to the harem, but instead buys Morgiane,

a woman more to his own taste, later drugging his master to preserve her virtue;

he later crosses paths with the thieves, discovering the location of the great

treasure they’ve accumulated and of the secret to access it (Open Sesame!)

enabling him to buy Morgiane’s freedom and return her to her father – who promptly

tries to sell her again – as well as his own freedom. Ali ultimately simultaneously triumphs

over the thieves, and over Cassim’s efforts to take the bounty for himself; the

treasure gets distributed to the masses (presumably to no lasting benefit) and

he’s left with Morgiane, who happily walks home through the desert as he rides alongside

her on horseback (an image of subjugation so blatant that it’s surely a joke).

The charitable explanation would be that Becker’s unexamined presentation of so

much venal materiality serves as its own quiet indictment (the director's preceding

film, the infinitely more highly regarded Touchez pas au grisbi, surveys

another milieu of calculating older men and their self-entitled relationships

with woman who earn their living on display), but that’s not particularly

apparent in a film that relies so much on Fernandel’s foregrounded mugging and

on easy colour and spectacle. One salvages whatever compensations one can – the

final advance on the cave is impressive by virtue of sheer human numbers, and

the movie throws gold coins around with happy abandon.

Thursday, May 20, 2021

Stripes (Ivan Reitman, 1981)

Ivan Reitman’s Stripes delivers a

familiar kind of ideological reassurance, of an American exceptionalism that

shines through when required, while being able to ignore all the lame strictures and

requirements that bog down gratification and self-expression. As depicted, the

army promotes absolute idiots into command positions and allows recruits to stumble

ineffectually through basic training, none of which stands in the way of

attaining personal and institutional greatness; it’s weird to be reminded of

the genuine stakes in the background (the proximity of the Eastern bloc and its

associated threat), however superficial the film’s depiction of that. It’s a

bit strange that the movie carries as much status as it does – Bill Murray’s

Bill Murray-ness is much more productively showcased in other films, and the presumed

comic highlights (like the scene in which John Candy’s character mud-wrestles

with various women) are more bizarre than funny. But even this much inspiration

seems absent from the final stretch, in which the Murray and Harold Ramis characters

use a top-secret military vehicle to rescue a bunch of their trapped comrades; for

whatever reason, things veer into James Bond territory as the bland-looking RV

reveals a plethora of destructive special features, causing all manner of explosive

mayhem without (as far as we’re shown anyway) leaving a single enemy combatant dead.

It’s a flatly-staged denial of reality that lines up against the treatment of

female soldiers - depicted as capable of stepping it up when required, but secondarily to their main function of giving it up for the guys (which is itself a

more elevated function than the alternative, of being ogled through telescopes while

in the shower). The movie pokes a couple of times at racial division, but always

pulls back immediately; it acknowledges homosexuality only in the form of a

jokey throwaway exchange early on. In the end, despite everything, Stripes

doesn’t even remotely question the traditional virtues of military service, leaving a pallid

aftertaste.