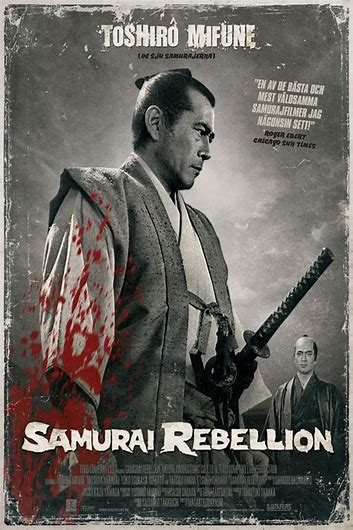

Masaki Kobayashi’s Samurai Rebellion

may sound in outline like a rather distanced and hermetic project: a family of

soldiers in the 1770’s, dutifully occupying its designated place within the

clan, is leaned on to betray its morality and instincts for the sake of a whim

of the clan lord, insisting that the family’s oldest son should marry his

discarded mistress; then later, after having accepted and even prospered from

the consequences of that, is asked to bend again when the whims reverse

themselves, and the clan lord wants her back. The film resonates now as a

study of the distorting workings of privilege and self-entitlement; time and

again, concepts of honour and propriety and simple human decency are shown to

be hopelessly malleable, the infrastructure that supposedly supports their

workings incapable of standing up to one man’s lust and ego (hello there, Republicans!). Toshiro Mifune is at his most resonantly moving as the family

head Isaburo, long weighed down by an unhappy marriage but now energized by his

oldest son’s happy one and by becoming a doting grandfather, finding liberation

in looming disaster (even declaring, as things close in, that he’s never felt

so alive). The film is finely sculptured throughout, with any number of

stunning individual shots, wringing a high quotient of nuance and feeling from

the genre’s non-naturalistic conventions. The satisfying ending culminates in a

fatally wounded Isaburo lamenting that he’s failed in his one remaining goal,

to ensure that the story of what happened would be told; the fact that it is

being told by virtue of the film’s existence provides a stray note of hope

among the absurd loss and desolation. Certainly there’s a rather lost in time

quality to the film – a few shots aside, it might as easily have been made in

1947 as in 1967 – but overall, that enhances its searching grandeur.

Thursday, June 15, 2023

Samurai Rebellion (Masaki Kobayashi, 1967)

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment