(originally published in The Outreach Connection in December 2004)

This is the fourteenth of Jack Hughes’ reports from the 2004 Toronto Film Festival.

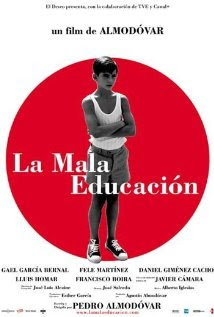

Bad Education (Pedro Almodovar)

Almodovar stands now at the peak of European cinema in the same way that Fellini, Bergman and Truffaut did in their heydays – like them, he wins Oscars (for both All About my Mother and Talk to Me) and his films attract people who don’t usually go to foreign films. And as with them, of course, there’s bound to be an ongoing debate about whether this preeminence is completely deserved. I wouldn't miss a new Almodovar movie for anything, unless it were a choice between that and a new Rivette, Akerman, Assayas or well, to be honest, quite a few other directors. There’s no Almodovar movie even close to making my DVD-worthy cut. But I confess I’m surprised to find myself writing this, because the recent films have been quite superb. Talk to Me, in particular, is a marvel of outlandish material spun into something rich and meaningful. But its smooth hum evokes a slight concern that Almodovar might be reducing trauma and joy and all else into a generalized benevolence – for now it resembles a philosophical state, but maybe it’s more like the avoidance of one. At the time, I thought the director’s next few films might be critical in establishing his place in the ultimate pantheon.

Sad to report then that Bad Education left me utterly cold. It’s another hall of mirrors plot with flashbacks within flashbacks and multi-layered motivations, all set out in the usual sumptuous gay milieu, but on this connection failing to forge any kind of emotional or thematic connection. The credit sequences feel like 60’s Hitchcock, and there are moments in the film that strongly evoke that director’s use of women (this being Almodovar, they’re enacted by a man in drag). More generally, the film is a kitsch film noir, with some minor Spanish social history as flavouring. I confess though that I make these observations as I might list the attributes of a pearl-bedecked ostrich – perhaps interesting on some hypothetical level, but not of much relevance to anything that’s going on today.

The plot has Gael Garcia Bernal as a struggling actor who brings a story to a famous director he knew in school – it recalls their treatment by a corrupt, molesting priest, with a layered-on epilogue of come-uppance. The director decides to make a movie out of it, hires the actor as the lead; then the priest (now a book publisher) turns up as well, with a different version of things. I confess that after a while I was drifting, and even as I write this a few hours afterwards, cannot recall the film’s intricacies with confidence.

“There’s nothing less erotic than an actor looking for work,” says the director at one point, which captures something of how I felt about the film’s hollow virtuosity. I doubt that Almodovar would care about anything I’ve written here – the film is surely not designed to be analyzed, although the twists and turns, presented with the vividness of revelation, sometimes feel like traumas pulled into the daylight by a flamboyant psychoanalyst. His view of mankind is generous and informed, but his characters know only desire, and movies, which increasingly seems insufficient. But Bad Education has also been acclaimed (albeit a little less than Talk To Her) so maybe there’s a substantial audience that knows only as much.

Keane (Lodge Kerrigan)

I often wonder what some directors do during their long absences from view. Since Stanley Kubrick died, we’ve had several accounts of the crazily meticulous research and deliberation that filled those five or ten-year gaps, but you can sense that gestation in Kubrick’s films, and anyway he could afford to stay at home. But what about a director like Whit Stillman, AWOL for six years since The Last Days Of Disco. Stillman seems much more pragmatic than Kubrick, and surely films like Metropolitan and Barcelona can’t have provided that big a money pot (maybe I’m being naive on this point) so where the hell is he? How does he keep it together, away from the camera for that long. What if he’s sick? What if he’s dead and no one knows it?

At least we can stop worrying now about Lodge Kerrigan, who hadn’t been heard from since Claire Dolan in 1998 – and since Claire Dolan never got released after the film festival, it might seem like even longer (I guess to the 99% of readers who’ve never heard of the guy, it might seem like a whole lot longer). It was a film about a prostitute, starring the late Katrin Cartlidge, and although it sometimes had the uncomfortable air of a male director trying too strenuously to assimilate the classic trappings of feminist filmmaking, it was still an interesting work, avoiding stereotypes and easy enigmas while carefully cultivating a cool ambiguity. To put this another way, the lead user comment on imdb.com is titled: “A bad, bad, bad, bad movie.” Maybe that’s why Kerrigan disappeared for so long.

Keane looks at times almost like an off the cuff project, but as it proceeds it acquires great deliberative power (although not quite six years’ worth). Damian Lewis plays the unbalanced Keane, who lives alone in a cheap rooming house, oscillating between quiet decency and outbreaks of clear mental illness. He says he had a daughter who was abducted, and is obsessed with finding her – he frequents the bus terminal where it happened, retraces his steps, runs through scenarios in his head. He meets an abandoned woman struggling to take care of her own daughter, who’s about the age of his own girl when she disappeared. He helps her out, and then the woman starts to rely on him for help with the girl while she tries to get her life back on track.

Hitchcock defined suspense as the opposite of surprise, being when you expect something to happen and it doesn’t. In that regard Keane is a suspenseful film, for the character is genuinely unpredictable, and you fear profoundly for the girl’s safety. But Kerrigan isn’t primarily after dramatic effect here. Actually the prime Hitchcockian echo is of Vertigo; like the second Kim Novak, the girl provides Keane a chance to redeem his earlier loss. Visually though, the style is grainy and closely observant, like the Dardenne brothers’ Rosetta or The Son, although the movie doesn’t quite have those films’ intense spiritual dimensions.

Hitchcock defined suspense as the opposite of surprise, being when you expect something to happen and it doesn’t. In that regard Keane is a suspenseful film, for the character is genuinely unpredictable, and you fear profoundly for the girl’s safety. But Kerrigan isn’t primarily after dramatic effect here. Actually the prime Hitchcockian echo is of Vertigo; like the second Kim Novak, the girl provides Keane a chance to redeem his earlier loss. Visually though, the style is grainy and closely observant, like the Dardenne brothers’ Rosetta or The Son, although the movie doesn’t quite have those films’ intense spiritual dimensions.Lewis gives an excellent, completely sustained performance, which seems to bear the marks of intense research; at the start, before its shape starts to emerge, the film seems entirely focused on assimilating the character, as though it were a case study. Ultimately it’s a strong visceral experience. It puts Kerrigan back on track to be a leading American director, but let’s be brutally frank – many of the greatest directors make films of twice the complexity of Keane in one third of the time. So his next move will be interesting.