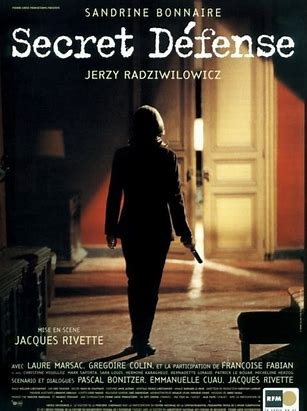

Near the start of Jacques Rivette’s Secret

defense, Paul Rousseau (Gregoire Colin) tries to steal a gun from his

sister Sylvie Rousseau (Sandrine Bonnaire); his target is the successful

industrialist Walser, newly suspected by Paul of killing their father, at that

time Walser’s boss, five years previously. It’s a classic Hitchcockian-type

set-up, and Rivette often plays it straight enough that the packaging of my old

DVD copy gamely tried to sell the film as a conventional thriller (“A father’s

death…A daughter’s obsession…Revenge was the only answer”). But of course, the director also

continually subverts any such genre expectations and norms: a train journey

which might easily have been condensed into a few seconds or less of screen

time extends over fifteen or twenty minutes; a key revelation about the dead

father is delivered almost casually, during another train journey; and so on. The

film has a sense of magnetic contraction, with all the characters being drawn

toward Walser’s country estate, a location with which the Rousseau family has a

long connection (and one of many such labyrinthine, figuratively haunted

locations in Rivette’s work); there’s often a sense of narrative echo, with the

father’s death recalling an earlier family tragedy along similar lines, and

with one key character who departs from the narrative rapidly replaced for most

purposes by a look-alike sister. Bonnaire’s often flinty, brittle performance

speaks to the strain of things not confronted within or without (an amusing

subplot involves a persistent suitor who she perpetually keeps at arm’s length,

without ever actually extinguishing all hope); the “top secret” of the title

refers as much to unexplored inner or cinematic possibilities as to the

specific folds of the plot. But overall, without buying into those marketing

excesses I cited, the film would indeed be a relatively accommodating entry

point into Rivette’s stunning cinematic world.