The Dolls (Bambole) is one of the many lesser-known anthology movies from 60’s Europe, this one with four directors but a mostly uniform tone (some of the best such anthologies benefit from a radically different contribution by Godard, but not this one). The common link in each case is frustrated sexuality, either prompted or suffered by one of the decade’s Euro-babes. In Dino Risi’s opener, Virni Lisi plays a wife who won’t get off the phone with her mother, eventually driving her ready-to-go husband into a more receptive set of arms in the adjacent apartment building. Luigi Comencini ogles Elke Sommer as she’s driven around in search of the genetically perfect Italian male to father her child, to the chagrin of the willing but rejected driver. Franco Rossi’s piece has Monica Vitti improbably married to a pathetic older drunkard, trying in vain to get someone to polish him off: the segment’s darker premise and Vitti’s recent association with Antonioni marks this as a somewhat more serious interlude, albeit still played as farce. Finally, Mauro Bolognini (in a story adapted from Boccaccio, as if that mattered) places Gina Lollobrigida as the unappreciated wife of a hotel manager; the hotel is full of priests attending an ecumenical conference, one of whom brings along his hot but oblivious nephew as his secretary, and so, well, obviously… This last segment may be the only one of the four in which the main players are all left fulfilled, without lasting consequences. The project may be scored as feminist-positive in that female desire is a stronger narrative driver here than the male; but on the other hand, the males just as often get what they want, not least of all those in the audience: the brassily fetishistic animation of the opening credits, and of course that title, say it all.

Saturday, November 30, 2019

The Dolls (1965, Dino Risi, Franco Rossi, Mauro Bolognini, Luigi Comencini)

The Dolls (Bambole) is one of the many lesser-known anthology movies from 60’s Europe, this one with four directors but a mostly uniform tone (some of the best such anthologies benefit from a radically different contribution by Godard, but not this one). The common link in each case is frustrated sexuality, either prompted or suffered by one of the decade’s Euro-babes. In Dino Risi’s opener, Virni Lisi plays a wife who won’t get off the phone with her mother, eventually driving her ready-to-go husband into a more receptive set of arms in the adjacent apartment building. Luigi Comencini ogles Elke Sommer as she’s driven around in search of the genetically perfect Italian male to father her child, to the chagrin of the willing but rejected driver. Franco Rossi’s piece has Monica Vitti improbably married to a pathetic older drunkard, trying in vain to get someone to polish him off: the segment’s darker premise and Vitti’s recent association with Antonioni marks this as a somewhat more serious interlude, albeit still played as farce. Finally, Mauro Bolognini (in a story adapted from Boccaccio, as if that mattered) places Gina Lollobrigida as the unappreciated wife of a hotel manager; the hotel is full of priests attending an ecumenical conference, one of whom brings along his hot but oblivious nephew as his secretary, and so, well, obviously… This last segment may be the only one of the four in which the main players are all left fulfilled, without lasting consequences. The project may be scored as feminist-positive in that female desire is a stronger narrative driver here than the male; but on the other hand, the males just as often get what they want, not least of all those in the audience: the brassily fetishistic animation of the opening credits, and of course that title, say it all.

Saturday, November 23, 2019

Near Dark (Kathryn Bigelow, 1987)

It may not be plausible to argue that Near Dark is Kathryn Bigelow’s best film, but if you could only keep one of them, it might sneak in (at the last charred minute before the arrival of the dawn, just as the last remaining print is on the verge of bursting into flames). The movie has a great, confident genre swagger, leaving out huge gobs of explanation and connective material: it takes what it wants from vampire mythology and discards the rest. Basically, that means no mumbo jumbo about crosses or waiting to be invited in or suchlike, and lots of hungry, malevolent glee – these certainly rank among the most zesty, committed vampires in the canon. That said, there’s not much actual bloodsucking, and the main instance of it – Adrian Pasdar’s newly-turned member drinking from the arm of the pretty girl who turned him (Jenny Wright) – is as intimate as it is malevolent. The film doesn’t exploit or objectify its female characters though: the troop seems to function in boisterously Hawksian manner, tolerant of quirks and difference as long as everyone pays his or her way. The narrative zips around the South, depicted here mostly as an underpopulated, dusty landscape of dingy motels, bus terminals, and nothing towns – it draws on the iconography of cowboys and family-centered homesteads, of heroic showdowns against the odds. As I indicated, the rising sun might constitute a major character in itself, at several points taking the rampaging vampires (who it seems don’t hit their stride until around 5.30 am) by surprise, sending them racing in search of shelter; no doubt the relish of one’s immortality coexists with a compunction to push its limits. Pasdar and Wright convey a quietly lovely, lonely connection that places them among the most appealing couples in a Bigelow movie (not that the competition there is too intense).

Saturday, November 16, 2019

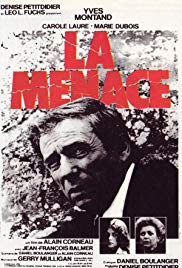

La menace (Alain Corneau, 1977)

Alain Corneau’s La menace plays out a cleverly-conceived scheme – a protagonist (Yves Montand’s Henri Savin) implicated in two non-existent crimes: the first a suicide in which his lover is implicated through coincidence; the second an elaborate ruse he devises as a route to freedom, but which works all too well, bringing him down through vigilante justice. Given all the complications, the film has relatively little dialogue, focusing primarily on action, from large-scale stunts on mountain highways to endless small manipulations: the typing of a faked letter, self-inflicting incriminating scratches, manipulating the hands of a clock and so on, the irony being that the underlying motive usually differs from the kind of malign set-up we’re used to in genre movies. In truth, it’s hard to figure out why Savin goes down this road in the first place, but perhaps the premise is that of an ill-considered initial reaction that then inexorably leads to others. The film’s climax plays out in British Columbia, where Corneau appears to have a great time marshalling heavy vehicles (this at the height of CB radio culture) on wide-open roads, although it doesn’t say much for the morals and ethics of Canadian truckers. The use of Montand in such a context presumably evokes The Wages of Fear, a movie that of course is infinitely better-remembered than La menace: for all of Corneau’s skill, the film feels rather uninvolving, partly because it’s hard to believe in the relationship between Savin and the beautiful, much younger cipher played by Carole Laure. The film hints that the investigating detective may contain his own more complex depths, but that just peters out, as does an initial subplot relating to human trafficking. Overall, it feels like Corneau’s precision and the climactic investment in spectacle should have resulted in a better-known film, but on the other hand the fate of excessive calculation leading to oblivion is an apt mirroring of its central narrative.

Saturday, November 9, 2019

Blow Out (Brian De Palma, 1981)

Blow

Out may be Brian de Palma’s most artful

indulgence of his affinity for disreputable material: it opens on an overly

prolonged, loving evocation of the slasher genre which might have been designed

to make your heart sink, but ultimately finds in such material a terrible kind

of commemoration, a recorded truth which for all its grisly artifice holds

greater integrity than the machinations of political power. The film has a classic

set-up: while capturing night noises from a bridge, Jack (John Travolta), a

movie sound guy, witnesses a presidential candidate’s car leave the road and

fatally enter the water, but no one subsequently wants to hear about the gunshot recorded on the tape, nor about the woman (Nancy Allen) he pulled from the sinking

vehicle. A large part of the pleasure comes from the immersion in old-fashioned

tangibility, in physically handling film, marking frames with an X and so on;

this and the title provide an obvious echo of Antonioni’s Blow Up, but

there’s not much of the aspirationally sensuous about De Palma’s film, not much

feeling of a time and place that will one day be looked back at with mysterious

fondness. Still, the situation allows plenty of pleasing ambiguities: for instance

in how Jack becomes the only repository of and fighter for the truth, even

though he only got into the whole thing while gathering raw material for

cinematic lies. The movie has some of De Palma’s most striking uses of split

screen, and a bravura climactic chase sequence; the narrative is well-crafted,

winding to a most bitter and incomplete kind of closure. One might wish that

Allen’s character could have been conceived in slightly more mature terms, or

that the political cover-up didn’t have to involve a gloatingly sleazy assassin

and a series of sex killings, but at least the movie’s colourful misogyny is in

step with its overall cynicism.

Saturday, November 2, 2019

Old and New (Sergei Eisenstein and Grigoriy Aleksandrov, 1929)

Eisenstein’s and Aleksandrov’s The Old and the New (or The General Line) makes now for astonishing if somewhat strange viewing, both enveloping and alienating. Following the evolution of a collective farm and the peasant woman who keeps pushing it forward, the film may stick in the mind largely as a series of set-piece milestones, such as the acquisition of the first milk separator, the first bull, the first tractor – the film establishes the specific economic significance of each step, while also positioning them as a form of dream-like release, so that the first spurting of cream becomes a fountain, one tractor becomes a formation of dozens, and the bull’s potency becomes (through a staged marriage to a flower-bedecked cow) that of the community as a whole (a visit to a modern state farm is positioned almost as a science-fiction trip to a smoothly facilitating future). But the scheme also encompasses cautionary near-nightmare: the initial application for the tractor drowns in gleefully-depicted bureaucracy, and there’s a stark evocation of witchcraft. The production history spanned a shift in governing ideology, and this results now in a film that always feels to be pushing to escape its propagandistic shackles, without denying their existence (or, to some extent at least, their validity). Few films contain as many vivid close-ups of care-worn faces, and in that respect it’s deeply humanly connected, but at other times it barely feels human at all (the villains and obstructionists often register more fully than the agents of progress). If viewed as history, then it’s a monument to a time when industrialization could be regarded as a tribute to the capacity of the land rather than as a pillaging of it; when physical labour could be alleviated without heralding a descent into narcissism; but at the same time it feels unshackled from any time and place at all, excepting that created through pure cinema.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)