Gene Kelly’s A Guide for the Married Man makes for mostly depressing viewing, if you regard the prospects for heterosexual marriage with even a scrap of romantic idealism. Paul Manning (Walter Matthau) is “happily” but aridly married and his thoughts drift to having an affair (perhaps with a neighbour; failing that just with anyone), egged on by his compulsively cheating neighbour Ed Stander (Robert Morse): the movie illustrates Ed’s advice on getting away with it with a series of sketches populated by “technical advisors” of the likes of Lucille Ball and Jack Benny. Some of the vignettes are moderately funny (although seldom very surprising), and at least the format provides an inherent degree of variety: Kelly’s direction is quite sprightly at times. But the society depicted here is a uniform existential wasteland in which a woman’s highest aspiration is to stay at home looking blandly beautiful and tending to her man and her children, all but extinguishing herself as a viable sexual being: for the husbands, it seems, the specific act of adultery is less significant than the prospective thrill of plotting to do it and the retrospective satisfaction of having gotten away with it (their lives being starved of any other compelling narratives). Everything is calculation and process, heavily aided by female gullibility and low expectations, enacted against a deadening materialistic backdrop: the ending in which Paul predictably “comes to his senses’ plays as fearful surrender more than happy awakening (Matthau in general seems rather depressed in the role, although that might be a form of commentary). It’s funny how many reviewers focus on the beauty of Inger Stevens in her role as Manning’s wife (“you have to wonder why Matthau would even consider adulterous behavior with a wife like Inger at home!”) as if this were a silly oversight of the film, rather than a proof of its toxicity.

Friday, March 27, 2020

A Guide for the Married Man (Gene Kelly, 1967)

Gene Kelly’s A Guide for the Married Man makes for mostly depressing viewing, if you regard the prospects for heterosexual marriage with even a scrap of romantic idealism. Paul Manning (Walter Matthau) is “happily” but aridly married and his thoughts drift to having an affair (perhaps with a neighbour; failing that just with anyone), egged on by his compulsively cheating neighbour Ed Stander (Robert Morse): the movie illustrates Ed’s advice on getting away with it with a series of sketches populated by “technical advisors” of the likes of Lucille Ball and Jack Benny. Some of the vignettes are moderately funny (although seldom very surprising), and at least the format provides an inherent degree of variety: Kelly’s direction is quite sprightly at times. But the society depicted here is a uniform existential wasteland in which a woman’s highest aspiration is to stay at home looking blandly beautiful and tending to her man and her children, all but extinguishing herself as a viable sexual being: for the husbands, it seems, the specific act of adultery is less significant than the prospective thrill of plotting to do it and the retrospective satisfaction of having gotten away with it (their lives being starved of any other compelling narratives). Everything is calculation and process, heavily aided by female gullibility and low expectations, enacted against a deadening materialistic backdrop: the ending in which Paul predictably “comes to his senses’ plays as fearful surrender more than happy awakening (Matthau in general seems rather depressed in the role, although that might be a form of commentary). It’s funny how many reviewers focus on the beauty of Inger Stevens in her role as Manning’s wife (“you have to wonder why Matthau would even consider adulterous behavior with a wife like Inger at home!”) as if this were a silly oversight of the film, rather than a proof of its toxicity.

Friday, March 20, 2020

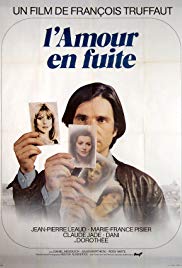

Love on the Run (Francois Truffaut, 1979)

Francois Truffaut’s frequent return to the character of Antoine Doinel seems on its face as a sign of commitment and identification, rendering it rather strange then how the Doinel films are generally among the director’s lighter and less substantial works. Perhaps this means they should be seen instead as a reliable means of escape, and yet they’re surely too self-reflective for that, and to a degree too self-revealing: it doesn’t take much research to discover, for instance, that the scene near the end of Love on the Run where two former girlfriends share their experiences of Antoine is cast with two former girlfriends of Truffaut himself (Marie-France Pisier and Claude Jade). Of course, that might suggest the movies are substantially an ego trip, but if so, it’s an exercise carried with a disarming sense of helplessness. Love on the Run, the last in the series, deals with Antoine’s divorce and other problems, and dwells along the way on other tragedies – the death of a mother, that of a child – but may feel overall like the breeziest of them all, which again may seem either like a failure of seriousness or a beguiling ambiguity. Take, for instance, the closing scene, in which Doinel wins back his latest squeeze by telling her, in the record store where she works, how he fell in love with her, on the basis of a photograph, before he physically met her: she yields to the story, of course, but as we the audience have already seen him recite the same story as the basis for an intended novel, it hardly lands as an emotionally committed outpouring. Especially not as the film then presents a pair of customers asking for a particular new release which is, in fact, the title song of the movie we’re watching. So it’s all a game, oscillating between poles, likely to leave the viewer quietly charmed and content, and almost entirely uninformed.

Saturday, March 14, 2020

Girl 6 (Spike Lee, 1996)

Watched again at a

time when questions of representation and inclusion only swirl more urgently,

Spike Lee’s Girl 6 is as intriguing and evasive as ever, a film of

finely seductive, sensuous presence (happily aided by a heavy Prince presence

on the soundtrack), built on long-established absences. It follows a young

actress, Judy (although we only learn that name in the final minutes), who out

of economic necessity becomes a phone sex operator, where “Girl 6” is her ID;

she starts to relish her popularity and her relationships with some recurring

callers, putting her sense of boundaries at risk. Theresa Randle is sensational

in the lead role, conveying all the character’s specific insecurities while

evoking a more classical, timeless mystique; the movie includes imagined

sequences in which she’s dropped into The Jeffersons, Foxy Brown, or Carmen

Jones, as Dorothy Dandridge, each of these serving both as celebration and

as an underlining of the limited coordinates of female black stardom. Dandridge

seems to constitute a particular preoccupation – the kind of pioneering icon to

which an actress might aspire, but whose career was hampered by cruel lack of

possibilities - and by bookending the film with two auditions at which Judy is

treated largely as a piece of flesh, Lee pointedly resists the sense of growth

and evolution that often attends such stories. As with the somewhat related Bamboozled,

an almost hallucinatory quality intercedes in the closing stretch, and the

final shot could be taken as much as a portent of future anonymity than as one

of triumph. Halle Berry briefly appears at herself, a few years before building

on Dandridge’s status as the first black woman to be nominated for the best actress

Oscar by becoming the first black woman to win it (and the only one to date) –

it’s a coincidence that fittingly underlines the sense of confinement and

restriction (as does Randle’s near-disappearance from movies for the last

decade).

Saturday, March 7, 2020

Redes (Fred Zinnemann and Emilio Gomez Muriel, 1936)

Fred Zinnemann and Emilio Gomez Muriel’s Redes is a completely absorbing hour or so of cinema – persistently stunning as observation of (at least apparently) real, challenged lives against pictorially transfixing backdrops, emotionally stirring for its depiction of social injustice, while also limited by narrative artifice and the unwarranted promise of its climax. The film focuses on a poor fishing community on the coast of Mexico, where one of the men becomes radicalized after losing a child for lack of money to buy medicine; he focuses on how the profit from their efforts flows overwhelming to the single capital provider at the top of the social pyramid, with the workers perpetually settling for almost nothing. He inspires some of his colleagues while alienating others, but in the end, after further tragedy, they’re all united, and the film suggests they might constitute a figurative revolutionary wave, amassing to wash away an exploitatively complacent society. The portrayal of the fishermen’s plight (interesting to note as an aside that women are barely glimpsed in the film, let alone being allowed to speak) feels as righteously provocative now as it did then, despite the mostly clunky portrayal of the complacent local master and his conniving politician sidekick. Among the multiple fascinating contributors to the film, the involvement of Zinnemann as co-director, long before his mainstream, multiple Oscar-winning peak, stands out: as with much of his later work perhaps, one can point to aspects of Redes which appear brave and ground-breaking, and feel grateful for its overall achievement, while yet feeling willing to sacrifice some of its craft and calculation (even Silvestre Revueltas’ grandly imposed musical score) in return for a more truthful overall testimony. But perhaps it took the test of time, and the repeated triumph of predatory capitalism, for that failure to become as clear as it is now.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)