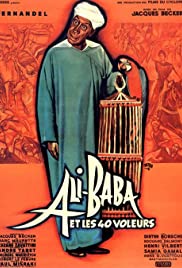

Looked at through modern eyes, Jacques Becker’s Ali Baba

and the Forty Thieves is something of a moral atrocity – a plot driven substantially

by slavery and exploitation, set in a world where the ruling class appear to

admit no challenge to their hegemony, and in which women have no rights other

than what relatively benevolent men might gift to them. Ali Baba is sent by his

master Cassim to buy a suitable woman to add to the harem, but instead buys Morgiane,

a woman more to his own taste, later drugging his master to preserve her virtue;

he later crosses paths with the thieves, discovering the location of the great

treasure they’ve accumulated and of the secret to access it (Open Sesame!)

enabling him to buy Morgiane’s freedom and return her to her father – who promptly

tries to sell her again – as well as his own freedom. Ali ultimately simultaneously triumphs

over the thieves, and over Cassim’s efforts to take the bounty for himself; the

treasure gets distributed to the masses (presumably to no lasting benefit) and

he’s left with Morgiane, who happily walks home through the desert as he rides alongside

her on horseback (an image of subjugation so blatant that it’s surely a joke).

The charitable explanation would be that Becker’s unexamined presentation of so

much venal materiality serves as its own quiet indictment (the director's preceding

film, the infinitely more highly regarded Touchez pas au grisbi, surveys

another milieu of calculating older men and their self-entitled relationships

with woman who earn their living on display), but that’s not particularly

apparent in a film that relies so much on Fernandel’s foregrounded mugging and

on easy colour and spectacle. One salvages whatever compensations one can – the

final advance on the cave is impressive by virtue of sheer human numbers, and

the movie throws gold coins around with happy abandon.