(originally published in The

Outreach Connection in December 2006)

Most critics regarded

Harsh Times, by David Ayer (who wrote Training

Day) as a minor entry in the urban drugs and violence genre, but I was

really surprised how much I admired it. Christian Bale and Freddy Rodriguez

drive endlessly around scuzzy LA, supposedly looking for jobs to mollify their

partners, but more preoccupied with getting high, making money however it

comes, and just creating mayhem. It’s a long and somewhat monotonous film, but

gradually reveals itself as a piercing, scathing study of two woefully

inadequate men whose irresponsibility might trip into frightening violence.

That Bale’s character is a troubled veteran going for a job with the Department

of Homeland Security gives it an effective broader undertone. In many ways Harsh Times is contrived and fanciful,

but it’s a rare film that can communicate any fresh perspective on macho

turmoil, and Bale gives one of the year’s most mesmerizing performances.

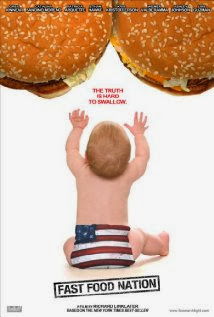

Fast Food Nation

Richard Linklater’s Fast

Food Nation is an interesting narrative derived from Eric Schlosser’s

devastating expose of the want-fries-with-that industry. I was never a big fast

food guy in the first place, but I have to report that Schlosser’s book

polished off whatever minor presence I ever had in the customer base. The film

may not be quite as effective, despite a final sequence that brings home the

visceral nastiness of what underlies it all, for the tone here is mostly

benumbed, as if crushed by the industry’s immense scale and the impossibility

of more than token gestures against it.

There are three main plot strands. One follows a head office

marketing executive (Greg Kinnear) investigating allegations of contaminated

meat from a supply plant; the second depicts illegal immigrants who keep the

factory wheels turning while being psychologically and financially exploited;

and the third shows a lower middle class family whose wellbeing is likely

permanently intertwined with the industry, indirectly if not directly, whether

they like it or not. At times the construction seems untidy and unsubtle, and

you feel that the wildly talented Linklater is being unnecessarily

self-effacing; I also wished he could have pushed the canvas a little wider

(the political dimension, for example, is mostly absent). But you might find

yourself thinking afterwards that the despairing, almost eerie undertone is

rather brave.

A Guide to Recognizing

your Saints was written and directed by Dito Montiel, based on his own

memories of growing up in New York in the 1980’s. The fact that Chazz

Palminteri plays his father may tell you all you need to know about the film’s

frequently familiar tone, although it is effective at conveying a sense of

turbulence and regret.

Kelly Reichardt’s Old

Joy is a small but highly effective study of two old friends, now mostly

grown apart, on an overnight camping trip. One of the men has greater

aspirations for the friendship than the other, and although the film is spare

and minimal, virtually every shot or line of dialogue is meaningful, creating a

moving portrait of the conflicting burdens of moving ahead, and of being left

behind.

The History Boys

The History Boys

is a lightning fast filming of the hit play that won this year’s Tony for best

play and actor (Richard Griffiths) after initially knocking them dead in

London. It’s set in early 80’s Northern England, where a group of teachers

tutor eight star pupils shooting for places in Oxford or Cambridge. The movie

is deliberately drab looking, but the language and the ideas are so

consistently eloquent and provocative that you feel an enormous sense of

transcendence. It’s often anachronistic and idealistic (a few critics have

questioned whether the boys would be singing Rogers and Hart songs rather than

tuning into the Human League or New Order, and their combination of rough-edged

laddishness and wildly well-read eloquence strains even theatrical license) but

I saw it mostly as a happy pragmatic fantasy, in which the malleable view of

history and learning ultimately extends into a highly fluid view of sexuality

as well. Crammed with aphorisms and metaphors, filtered through just about

perfect performances, it’s a valuable record of what must have been an even

more striking experience on stage.

Emilio Estevez’s Bobby

follows a bunch of characters milling round a California hotel on the night

Robert F Kennedy got shot in 1968. The film was disparaged in some quarters as

a cousin to Fantasy Island or The Love Boat, with mostly fading stars

(Demi Moore, Sharon Stone, Anthony Hopkins and many more) acting out

conventional personal dramas: affairs, weddings, fears of mortality, alcoholism

– it’s all here, competently written and performed competently but never coming

close to anything distinctive or revealing. The point seems to be something

about brotherhood and the importance of moving past violence. Estevez’ ambition

far exceeds his achievement, but at least it’s smooth and watchable (and of

course achingly sincere) – better than The

Love Boat, but worse than a whole lot else on TV.

Volver

Pedro Almodovar’s Volver

continues his evolution into a benevolent, almost cuddly mainstream auteur the

like of which hardly exists any more. This celebration of female adaptability

stars Penelope Cruz in Sophia Loren-like mode as a struggling, earthy Madrid

housewife who’s hit by everything at once: old secrets coming back to life,

family crises galore, all framed by a loose network of women doing what it

takes to get by. It’s all dressed up like a chocolate box, but as always with

Almodovar, the material is remarkably raw at times – how many directors could

throw in a revelation of incest with such limited histrionics? The film is a

joyous, superbly controlled melting pot – spirituality and sexuality, austerity

and full bloom, the murky past jostling against the vivid present. Men hardly

figure in the film’s scheme, except as dispensable bastards – a contrivance

that contributes to my overall feeling that this ranks below highpoints like Talk to Me. Still great stuff though.

Recently I’ve been finding myself at the Bloor Cinema more

often in years, reflecting an excellent series of Toronto premieres - Mutual

Appreciation, Old Joy, and then Bent Hamer’s Factotum. Factotum is

certainly the least of those three, but it’s a highly engaging viewing

experience. It’s based on a novel by Charles Bukowski, depicting a

fictionalized version of himself drifting between jobs and women and from drink

to drink, all of which somehow powers his writing jones. Matt Dillon channels

the young Jack Nicholson in the lead role – laid back often to the point of

catatonia, impudent, sometimes brutally violent and self-righteous. It’s a very

entertaining stylized creation, and the film pretty much takes his lead. But

compared to Marco Ferreri’s Bukowski adaptation Tales of Ordinary Madness, which I watched again recently, Factotum doesn’t feel sufficiently

cohesive. It’s always a mystery how the guy holds it together; we don’t glean

much sense of what it is he’s writing; and the film feels sparse, almost

abstract, lacking any real low-life flavour. But it’s also full of striking,

often funny moments.