(originally published in The Outreach Connection in March 2008)

In my Oscar

predictions article back in February I moaned about not feeling the vibe this

time – it all seemed so predictable, I said. But then it ended up producing one

of the freshest and most worthy lists of winners in years. Whatever one’s

reservations about No Country for Old Men,

it’s obviously not a “safe” or bland choice in the much-mocked tradition of Oliver! et al. So I ended up enjoying it

after all. And look at the progress that’s been made in secondary trouble

spots. Best song no longer gets automatically mailed over to Disney. Best

documentary shows an increasing affinity toward, well, good documentaries. Best

sound effects editing…well, I’m sure that one always hits the spot too.

Dubious Winners

The focus of

discontent this year, as it often has been in the past, was the best foreign

film category. One commentator after another lambasted the process for

excluding (in particular) the Romanian 4

months, 3 weeks & 2 days from the nominations, and derided the chosen

nominees as a group of musty second-raters. They certainly sounded that way,

although given that virtually no one had seen the films at that point, the

criticism might have been a little unfair. As it turned out, the eventual

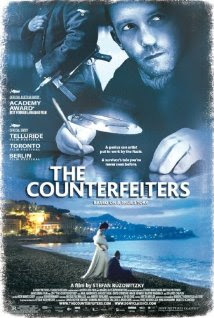

winner, The Counterfeiters, seemed to

be admired by just about everyone. More on that below. But it’s no 4 months, 3 weeks, 2 days.

Just as, in 1977, Madame Rosa was no That’s Obscure Object Of Desire. Or in 1966, A Man and a Woman was no Battle

of Algiers. And so on. But Bunuel and Pontecorvo beat the odds big-time in

even getting to that stage. What’s most wretched about the category is the

plethora of utter dross, winners that barely even registered at the time, let

alone subsequently. How about 1982’s To

Begin Again? Or 1984’s Dangerous Moves?

Where do they find this stuff? And the stuff they beat was, for the most part,

of the same ilk. Mostly no-name filmmakers who hit the jackpot (this being an

apt metaphor for the apparent correlation of success and merit). Meanwhile, the

list of names that never got in sight of a nomination is staggering: Godard,

Ozu, Bresson, Tarkovsky, Hou…and it goes on and on and on.

Over the years a

few directors, closely corresponding to the traditional canon of great

art-house filmmakers, have made it through the process (although usually for

lesser works): Bergman (3 times), Fellini (twice), Kurosawa and Truffaut (once

each). A few recent winners – All about

my Mother and The Lives of Others

– were actually the year’s best

foreign film (or at least one of the best) for many viewers. But then you ask

yourself who might be the best foreign directors of our time, and it’s pretty

clear that Caroline Link, Gavin Hood and Stefan Ruzowitzky wouldn’t be on the

list. They do have Oscars though.

Flawed Process

The problem seems

to be twofold. First, unlike most of the other awards, the foreign film

nominees don’t even represent an attempt, on anyone’s part, actually to survey

the year’s world cinema and pick a sampling of the best. Every country submits

a single nominee, selected as it sees fit (so that for example, the limping

Kazakh industry gets as big a shot as the somewhat richer depths of French

cinema). Therefore many notable films are never in the game (for example, La Vie en Rose, despite its best actress

victory, never had a shot at best foreign film because the French submitted Persepolis instead). Films that straddle

two or more countries may never get selected by anyone. Then, of course, there

are endless eligibility rules. This year’s The

Band’s Visit was reportedly disqualified this year for having too much

English dialogue. Well, it’s a group of Egyptians in the middle of Israel –

that’s the only language they have in common! Doesn’t verisimilitude count for

anything?!

Secondly, again

unlike the other Oscars, the award doesn’t get voted on by the Academy’s

general membership. A committee hones down the submissions (this is where 4 months fell by the wayside) to pick

the five nominees, which can then only be voted on by members who’ve viewed all

five in movie theatres (not, as they increasingly do for many other categories,

on DVD). Who know how dramatically that whittles down the membership? Maybe

it’s just a dozen people, mostly retirees. I certainly doubt Jack Nicholson

gets to vote most years. (The prevailing theory is that the committee just

didn’t get 4 months – too edgy, not

obviously well crafted in the traditional sense – and certainly didn’t care for

the abortion material).

There’s some

theoretical merit to all this of course – primarily to ensure that small

countries aren’t crowded out by big ones. But the process I described, by its

nature, doesn’t constitute any rational evaluator of merit. It’s more analogous

to having a group of loosely knit acquaintances select the destination for a

collective night out. No matter how adventurous some of them feel on a given

evening, if it’s an Olive Garden kind of bunch, you’re not going to sell them

on Susur.

The Counterfeiters

Well, that was

time well spent: until that whole process is scrapped and replaced by something

more broad-based, I’ll be able to recycle this article every year (with a few

token updates) and it’ll always be right on the money. So how does The Counterfeiters rack up against this

sad history? I’d say somewhere in the middle of the pack. It’s a good enough

movie, but in a very familiar manner. Nothing about it startles you - the technique is solid but not at all

distinctive, the themes are interesting but well trodden. It’s not even close

to being the best foreign film of the year, although I grant it may be the best

Austrian film of the year,

Directed by

Ruzowitzky, it’s set primarily in a 1944 concentration camp, where an

imprisoned counterfeiter is put to work by the Nazis to manufacture vast

quantities of pounds and dollars, initially to undermine the Allies’ economies

but later on to finance the collapsing German war machine. Someone pointed out

the parallel to Bridge on the River Kwai

– the desire to stay alive, and an innate sense of professionalism, fights

against the shame of providing such massive assistance to the enemy.

I don’t mean to

dismiss the film at all – there are many subtleties here. The central

character, played by a ratty-looking Karl Markovics, is a finely conceived

study in conflicting motives and beliefs. The film is almost a chamber piece –

well treated up to a point and isolated from the other prisoners, the team of

counterfeiters experiences the ongoing war mostly as overheard gunshots,

screams, as fragments of news. And it flirts subtly with the situation’s black

comedy without ever distilling its horror. As I write, I saw it two weeks ago,

and it’s almost already forgotten.

No comments:

Post a Comment